A few days ago, someone leaked a draft of the Education Department’s proposed new Title IX regulations. The document seeks to use federal authority to ensure that universities employ fairer procedures when adjudicating sexual misconduct claims. Today, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos—quite appropriately—took a different approach to the issue of free speech on campus. Rejecting the idea of a “speech police” from the Department of Education, DeVos instead used the power of the bully pulpit to urge universities to create an environment that welcomes discourse, even on controversial issues.

DeVos’ Constitution Day speech worried that “precious few campuses can be described” as promoting a “free and open” intellectual environment. She cited several examples; perhaps the most troubling of her list was last year’s incident at William & Mary University, where Black Lives Matters protesters successfully shut down a talk—intended to celebrate free speech and the First Amendment!—by a representative of the ACLU. (Reason’s Robby Soave had excellent coverage of the affair.)

DeVos sharply criticized administrators for too often seeking to undermine, rather than promote, free speech on campus. (She especially worried about what she saw as the abuse of security fees as a way of shutting down controversial speakers whose views might challenge the perspective of the campus majority.) Administrators, DeVos feared, too often “attempt to shield students from ideas they subjectively decide are ‘hateful’ or ‘offensive’ or ‘injurious’ or ones they just don’t like”—a patronizing approach that the Education Secretary convincingly argued harms, rather than enhances, a typical student’s educational experience.

Instead of a relativistic environment, DeVos urged campuses to refocus their missions on a pursuit of truth. She celebrated the efforts of Princeton’s Robby George and Cornel West to promote open discourse even as they disagree about most political issues. She urged universities to adopt the University of Chicago principles on campus free expression. In perhaps the most intriguing portion of the address, DeVos proposed a test called “Haidt’s choice”—named for NYU’s Jonathan Haidt—contending that schools need to choose between pursuing truth and pursuing harmony. It simply isn’t possible, the Secretary implied, for a university to remain devoted to the truth while focusing on “social justice”—given that the “social justice” approach presumes that some ideas (even true ones) would contradict the university’s mission.

Regarding campus due process, DeVos has correctly concluded that absent direction from Washington, schools will not act on their own to create fairer procedures. Her approach to free speech, by contrast, sees a limited role for Washington and recognizes that, ultimately, the burden is on administrators, faculty, students, and trustees to ensure that universities live up to their ideals. No government, she recognizes, “can force its people to be responsible.”

In our polarized time, DeVos’ speech doubtless will attract criticism from political foes of the administration. And given that she serves a President whose relationship with the truth is, at best, distant, the administration is an imperfect vessel for her Constitution Day message. But, as with her promotion of campus due process, DeVos’ celebration of a more open campus intellectual environment merits support from liberals and conservatives, and Republicans and Democrats, alike.

Read the text of Secretary DeVos’ speech to the National Constitution Center, September 17, 2018, below:

Thank you for commemorating this day. Constitution Day brings focus to the importance of civic education and its essential role in the health of our constitutional republic.

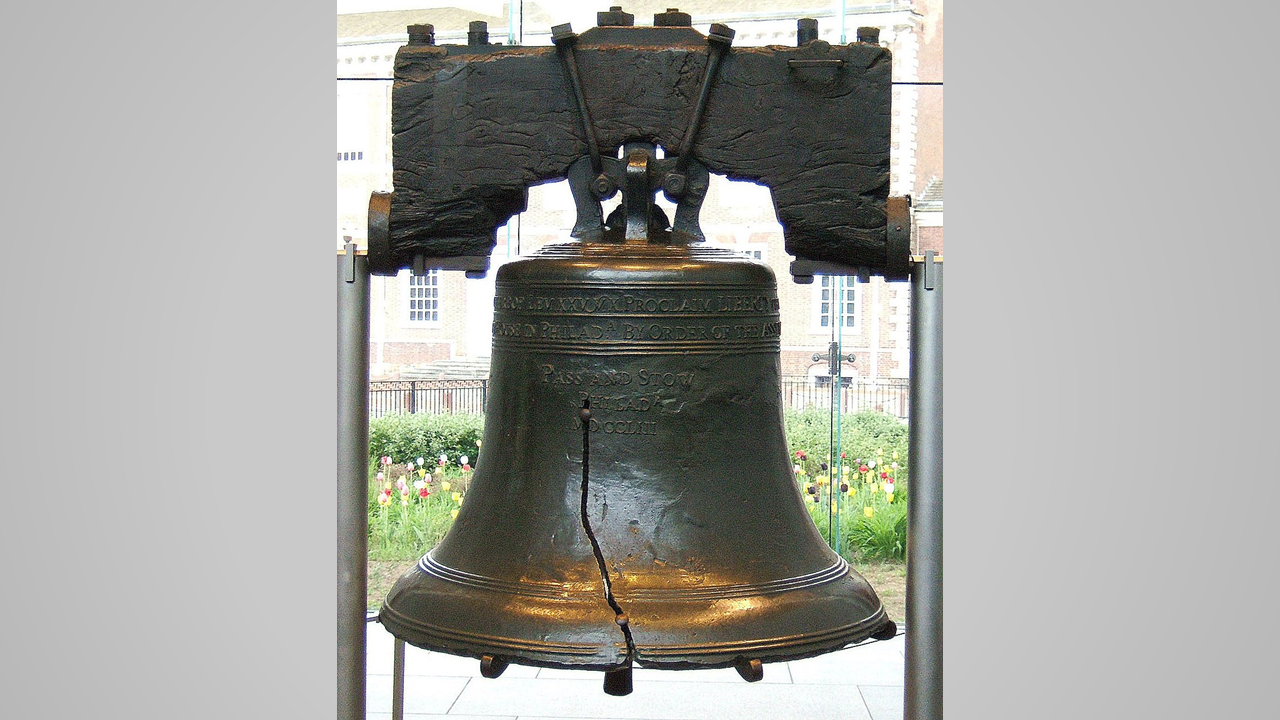

Our Constitution became the standard for freedom-loving people throughout the world by design, not by accident. The Framers gathered just a few steps from here 231 years ago – willingly and freely – to discuss, debate and propose to the states a national government that would restrain itself by empowering its people.

I’m honored to be here to discuss some of the first restraints placed on government by our Bill of Rights. Our “first freedoms” – and what we do with them – shape our lives. The freedom to express ourselves – through our faith, through our speech, through the press, through assembly or through petition – defines much of what it means to be human.

This freedom, preserved in our Declaration of Independence, comes from the truth that our rights are endowed by our Creator, not by any man-made government.

And for a time, that was… “self-evident.” But along the way, these Founding principles have been taken for granted. Today, freedom – and the defense of it – is needed more than ever, especially on our nation’s campuses.

The fundamental mission of formal learning is to provide a forum for students to discover who they are, why they’re here and where they want to go in life. These are formative years: times and places to learn, to be challenged, to grow and to make mistakes. Learning is enriched by what each individual student brings to that experience…

… if – and only if – that environment is free and open.

Today, precious few campuses can be described as such. As the purpose of learning is forgotten, ignored or denied, we are inundated daily with stories of administrators and faculty manipulating marketplaces of ideas.

Take what recently happened to a student at Arkansas State University. She wanted to recruit for a student organization she was founding, but soon learned it first had to be approved by the university. Even then, she still had to apply for a permission slip to distribute materials.

And all of the activity had to occur within the confines of a “speech zone,” typically obscure, small, cordoned-off corners of campus where free expression is “permitted.” These so-called “free speech zones” are popping up on campuses across the country, but they’re not at all free

The Arkansas State student proceeded to set up shop, and was promptly removed by a university administrator and a campus police officer. She’s suing, and a judge recently allowed the action to proceed.

Students at Lawrence University in Wisconsin recently hosted a screening and discussion of a documentary that warns of the threat modern sensibilities pose to comedians, to their humor and ultimately, to their speech. When the event was announced, it sparked passionate and disruptive protests which continued into the screening itself.

As a private university, Lawrence is not directly bound by the First Amendment. But it had promised its students free expression “without fear of censorship or retaliation.” Yet the university ultimately denied official recognition to the student group that had hosted the screening. Ironically, the student group’s name was “Students for Free Thought.”

The screening at Lawrence University continued in spite of interruptions, but not all student events are so lucky. An official student activities board at the College of William & Mary, a public campus in Virginia, recently hosted a director of the American Civil Liberties Union for a discussion on free speech. Almost as soon as the event got underway, students rushed the stage and began to shout down the ACLU representative, an organization typically allied with many of the same causes shared by those who were shouting. The event never resumed.

College administrators vowed to remedy the situation, but the “heckler’s veto” had already prevailed.

This veto has been used against me, as well. More than a few institutions have been unwilling to provide a forum for their students to discuss serious policy matters that affect our country. I can and have found other forums, but what about students who cannot?

Too many administrators have been complicit in creating or facilitating a culture that makes it easier for the “heckler” to win. One prevalent way is when administrators charge students exorbitant fees to host an event or speaker they arbitrarily deem “controversial.” This way, administrators can duck accusations of censorship based on content and instead claim that reasonable “time, place and manner” restrictions are appropriate.

But just ask students at the University of Michigan for more on that. When students invited Alveda King, the niece of Martin Luther King, Jr., to speak on campus, administrators forced the group to have public safety officers patrol the event. There were no disruptions, but students were billed hundreds of dollars for the security anyway. Students elsewhere have been forced to pony up thousands in “speech taxes” for hosting speakers on campus.

The examples could go on and on, but I think the point is clear: When students come to learn, they too often encounter limits on what, when, where and how they learn.

Administrators too often attempt to shield students from ideas they subjectively decide are “hateful” or “offensive” or “injurious” or ones they just don’t like. This patronizing practice assumes students are incapable of grappling with, learning from or responding to ideas with which they disagree.

Such limits on freedom are sometimes subtle, other times they are noisy. But both are rampant and both are bad.

And all too often, students do not learn about our Constitution and our freedoms in the first place. I think of a survey conducted some years ago by Philadelphia’s own Museum of the American Revolution. It found then that 83 percent of Americans did not have a basic understanding of our Founding. In fact, more Americans knew that Michael Jackson wrote “Billie Jean” than knew who wrote the Bill of Rights – or even that those Rights are amendments to our Constitution.

What does that say about America’s schools? According to the 2014 Nation’s Report Card, only 18 percent of eighth graders had a proficient knowledge of American history. And in previous years, high school seniors did even worse: only 13 percent were proficient or better.

Just think about the real-world consequences of those sobering statistics.

When students don’t learn civics or how to think critically, should anyone be surprised by the results of a recent Brookings Institution poll? It found that over half of students surveyed think views different from their own aren’t protected by the Constitution. Is it any wonder a growing number of students also say it’s OK to shout someone down when they disagree? And is it any wonder too many students even think that violence is acceptable if you disagree with someone?

Now, disagreement about deeply held beliefs can certainly fuel passions and raise decibels. But violence is never the answer. No one should confuse the right to speak with an invitation to use force. Administrators may think they’re doing their part to reduce tensions by censoring certain ideas, but in fact, doing so often inflames them.

And the way to remedy this threat to intellectual freedom on campuses is not accomplished with government muscle. A solution won’t come from defunding an institution of learning or merely getting the words of a campus policy exactly right. Solutions won’t come from new laws from Washington, D.C or from a “speech police” at the U.S. Department of Education.

Because what’s happening on campuses today is symptomatic of a civic sickness.

The ability to respectfully deliberate, discuss and disagree – to model the behavior on display in Independence Hall – has been lost in too many places. Some are quick to blame a “tribalization” of America where groupthink reigns. Others point to the rise of social media where, under the cloak of anonymity, sarcasm and disdain dominate.

Certainly, none of that improves our discourse. But I think the issue is more fundamental than that. And it’s one governments cannot solve.

The issue is that we have abandoned truth.

Learning is nothing if not a pursuit of truth. Truth – and the freedom to pursue it – is for everyone, everywhere. Regardless of where you were born, who your parents are or your economic situation, truth can be pursued and it can be known. Yet, students are often told there is no such thing.

A RAND Corporation study recently found an alarming “truth decay” in American public discourse. One culprit was identified as a “relative volume and resulting influence of opinion and personal experience over fact.”

I think of the teacher who blithely wears a shirt that reads: “Find your truth.” Poor advice that is plastered on the walls of the classroom for her unsuspecting young students to absorb, as well.

That notion has taken root in our relativistic culture. Surely we’ve all heard something that goes like this: “You have your truth. And I have mine.” Folks who embrace this notion insulate themselves from other people, other experiences and other ideas. Serious conversation is over.

The pernicious philosophy of relativism teaches that there is no objective truth. Nothing is objectively good or objectively evil. “Truth” is only personal point of view, fleeting circumstance and one’s own desires. And those views, those experiences, those desires can be understood only by those who live them. Nothing else and no one else matters.

And that, I posit, is the threat that America’s campuses face today. Our self-centered culture denies truth because acknowledging it would mean certain feelings or certain ideas could be wrong. But no one wants to be wrong. It is much easier to feel comfortable in saying there is no truth. Nothing that could challenge what we want to believe.

But learning is about thinking, reasoned argument and it’s also about discovering facts. If ultimately there are no facts – if there is no objective truth – then there is no real learning.

Abandoning truth creates confusion. Confusion leads to censorship. And censorship inevitably invites chaos on campuses, and elsewhere.

This is not simply a matter for academics to debate. Parents are watching how institutions of learning are resolving these controversies, and many don’t like what they see. Recent surveys indicate public support for colleges and universities has declined over the last few years.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. There are alternatives.

Let me offer a few thoughts in this regard.

Begin with yourself. In our fast-paced, noisy world, it is healthy to develop an interior life. Be still, pray, reflect, review, contemplate. Starting with ourselves – with introspection – would help us approach each other with more respect and grace.

Then listen – really listen! – and then personally engage those with whom we disagree. It’s easy to be nasty hiding behind screens and Twitter handles. It’s not so easy when we are face to face. When we are, we more quickly recognize that behind each strongly-held idea are heartbeats, emotions, experiences… in other words, a real person.

And if we use our two ears proportionally to our one mouth, we can speak with conviction when we’re certain and listen with intent when we’re not, humbly leaving open the possibility that even when we feel quite certain, we might be quite wrong.

We would also do well to rightly understand the responsibility that goes along with freedom. Yes, free speech is both a right and a responsibility. Saint John Paul II said it well: “freedom consists not in doing what we like, but in having the right to do what we ought.”

His reminder is fitting today, because… we’re not all saints! We won’t always do the right thing. We will make mistakes. We will say the wrong things and subscribe to the wrong ideas.

There are bad ideas. I’ve had a few, and heard more than a few myself. But the exchange of ideas should be conducted openly, where good ones can rightly defeat bad ones – with open words and open dialogue, not with closed fists or closed minds. John Stuart Mill wrote that anyone “who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that.”

To that end, we can embrace a Golden Rule of free speech: seeking to understand as to be understood. That is to say, a willingness to learn from any idea, even ones with which you disagree or ones that aren’t your own. It’s also the humility to listen with the understanding that you yourself might be mistaken.

A responsible use of free speech, in this sense, is a desire to prove why your ideas are better for your neighbor because you love your neighbor, not because you only want to prove him or her wrong.

I think often – even more so this past week – of phrases my father-in-law used all the time. Among them are: “I’m wrong.” “I’m sorry.” “Thank you.” “I respect you.” And “I love you.”

Some folks get this right. Princeton’s Robby George and Harvard’s Cornel West don’t agree on much. But the two professors recently wrote an instructive statement about freedom of thought and expression.

“All of us,” they wrote, “should be willing – even eager – to engage with anyone who is prepared to do business in the currency of truth-seeking discourse by offering reasons, marshaling evidence, and making arguments.”

The two professors respect the freedoms of students to express themselves through peaceful demonstrations, but, they ask, “Might it not be better to listen respectfully and try to learn from a speaker with whom I disagree? Might it better serve the cause of truth-seeking to engage the speaker in frank civil discussion?”

Those are important questions. At least one university is leading the way in addressing them. Since its founding, the University of Chicago has always affirmed a commitment to free and open inquiry. A committee there recently reaffirmed that commitment in a statement of principles – not new policies or codes.

In its report, the committee wrote that the University “guarantees…the broadest possible latitude to speak, write, listen, challenge, and learn.” The committee rightly suggests “It is for the individual members of the University community, not for the University as an institution, to make…judgments for themselves, and to act on those judgments not by seeking to suppress speech, but by openly and vigorously contesting the ideas that they oppose.”

More institutions would do well to adopt the University of Chicago’s statement and embrace its approach.

Others look to Yale’s 1974 “Woodward report” on free expression. Without sacrificing the pursuit of truth, the report’s authors explain, “[an institution of learning] cannot make its primary and dominant value the fostering of friendship, solidarity, harmony, civility, or mutual respect.” Instead, those priorities are “responsibilities assumed by each member of the university community, along with the right to enjoy free expression.”

Too many institutions have tried to pursue truth and harmony, but end up failing in both. Jonathan Haidt, a psychologist and professor at New York University, argues that institutions of learning cannot pledge to pursue truth and at the same time oblige “a welcoming atmosphere,” “civility” or even “social justice.”

The latter are to be voluntarily embraced by each member of the community. A school, on the other hand, must make a choice as to its purpose. Let’s call it “Haidt’s choice.” Pursue truth or pursue harmony. An institution of learning cannot be both a forum for all ideas and an advocate for some at the expense of others.

And learners have a choice to make, as well. No school and no government can force its people to be responsible. That’s something individuals must freely and consciously choose on an ongoing basis.

True freedom is ultimately ordered toward virtue and responsibility. Freedom detached from truth and disconnected from virtue isn’t freedom at all.

America is exceptional because of her freedoms. Not simply because they are in the Constitution’s text, but because they are an intrinsic part of who we are. The world knows that, and craves it. Thousands upon thousands of people risk everything to escape tyranny and flee to the United States for a better life… for freedom. But “if we lose freedom here,” Ronald Reagan warned, “there is no place to escape to.”

America is the hope for the world. Let’s resolve to get back to believing in and living out our freedoms in ways our Framers – and our Creator – designed. May we forever cherish, teach, exercise and protect our God-given freedoms. Thank you for having me here today. I look forward to our conversation.

I have just decided that here in Illinois I am going to petition my State Representative and Senator to pass a bill that requires each State university and college to adopt the University of Chicago principles on pain of a 10% reduction in their budget each year they fail to do so.

The old joke was that there was Freedom of Speech in the Soviet Union, but in the United States there was Freedom after Speech…

Freedom of Speech will not exist in academia until there is Freedom AFTER Speech — and that means reigning in the Behavioral Intervention Teams and to stop treating those saying politically incorrect things as imminent threats to campus safety.

Otherwise, everything else is moot — as the Soviet Constitution of 1977 did technically guarantee freedom of speech.