Really, you must admit that student protestors are becoming ever more adorable, kind of like naughty children who first act rambunctiously and then go running back for comfort to the elders they’ve just annoyed. The latest case in point is laid bare in a series of articles in Duke University’s campus paper The Chronicle.

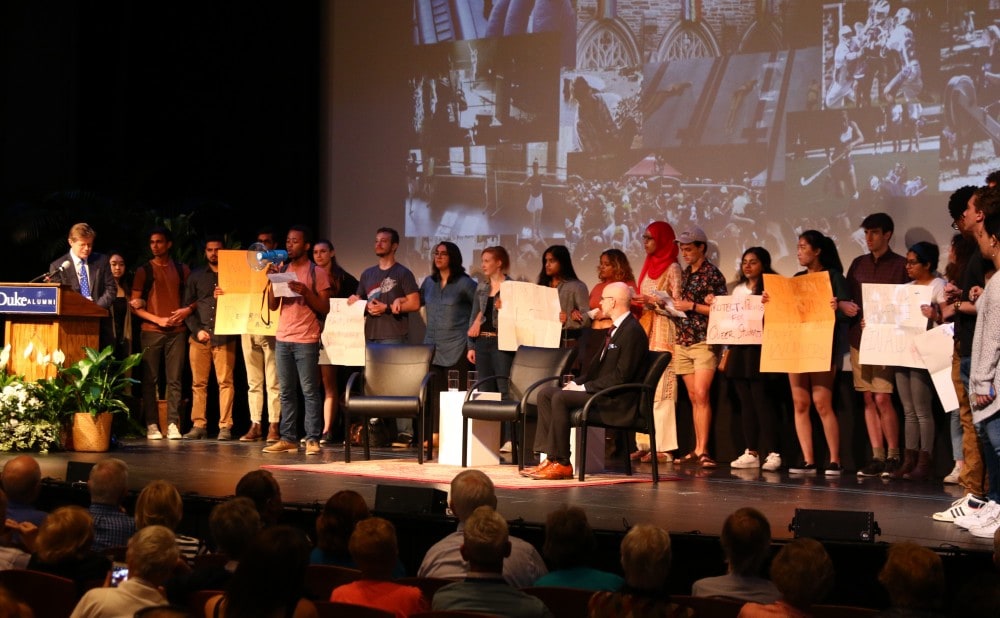

It all started on April 14, when, despite warnings from the administration that any student disruption would lead to consequences, about two dozen students took over an alumni event. They used a megaphone to shout down Duke University President Vincent Price as he addressed a group of alumni at the long-planned commemoration of the 50th anniversary of a series of student sit-ins at Duke in 1968.

Price, who has been president of Duke for just one year, had already signaled his good intentions in many ways. Although Price used the hallowed word “diversity” only once in a speech to the Academic Council on March 22, 2018, he had noted proudly that with some recent new appointments, “eight of our ten Deans will be women. We truly have a bright future ahead.”

The students’ own vision for Duke’s future, however, evidently required what they later called a public show of their “activism,” which wasn’t satisfied by the mere creation of a manifesto nor by an invitation that they participate in some panels scheduled for the alumni event. Instead, they wanted to “actually live out our truth” by commandeering the stage.

This sounds brave enough, given that they were undeterred by Duke’s policy, of which they had been reminded by leaflets circulated before the event. The university’s Pickets and Protests Policy is crystal clear: “The substitution of noise for speech and force for reason is a rejection and not an application of academic freedom,” the policy plainly declares. “A determination to discourage conduct which is disruptive and disorderly does not threaten academic freedom; it is rather, a necessary condition of its very existence.” Violations of this policy trigger an investigation and hearing before the University Judicial Board.

But the students knew better than to take this seriously. A week-long occupation of a building in 2016 had indeed resulted in the initiation of formal misconduct proceedings, but these were later dropped.

Among the students’ demands (which included higher minimum wages and hiring more faculty of color) was that more money be devoted to counseling services. This last is a particularly interesting detail, given what transpired after the event.

First, to the students’ chagrin, not all the alums present at last month’s event were happy with the disruption. Some in the audience booed loudly, stood and turned their backs to the stage, voiced vulgarities and even (so said the protesters) used racial epithets, all of which was personally painful to the protesting students.

But worse was to come: The administration decided to enforce its own policy and the Office of Student Conduct sent letters to about 20 students announcing that an inquiry of their conduct was underway.

In an interview with the Duke Chronicle a few days later, three organizers of the disruption expressed their distress: “Instead of actually going to the alumni and saying, ‘that’s not appropriate’ or removing them from the space, they [administrators] were more worried about [our behavior],” one said.

Furthermore, receiving official letters regarding their conduct was “somewhat traumatizing.” One of the organizers even warned that these letters “will be exacerbating any preexisting mental health conditions . . . and starting new ones.” Why, he wondered, wasn’t the university “reaching out to us in good faith rather than initiating a conduct process.” It was their manifesto with its numerous demands that should be attended to, not their conduct. After all, their document “is the response to years and years and patterns and systemic injustices.” How could they fail to be frustrated that administrators “aren’t even engaging with us directly,” aren’t appreciating that “this is an opportunity for dialogue and for policymaking” that will benefit the entire university.

So, first comes the disruption, then the expectation that the university should react with good faith, dialogue, and outreach. Somehow, the disappointed students “expected better from the administration,” since the students too were acting out of concern above all with Duke’s future.

One student touchingly and perhaps inadvertently revealed that he viewed students and adults as two separate groups: “In terms of adults who have reached out to us, whose job is to care for us, they just haven’t, and so we’ve been holding each other up.” But campus reactions weren’t all bad news, for “the statements of solidarity from other folks are keeping us going.”

Some faculty members, of course, got into the act. More than 100 signed a letter urging no disciplinary action be taken against the student disrupters and asking administrators “to try to resolve these issues through discussion [rather] than risk continued conflict between students and the university’s administration.” And, like the protesters themselves, the letter notes the similarity between the recent disruption and the 1968 sit-ins being celebrated at the alumni reunion.

Perhaps these faculty members have been chastened by an instantaneous rush to judgment in a 2006 case when three men from the Duke lacrosse team were accused of gang rape by a stripper performing at a party. In that notorious instance, a Group of 88 professors signed a credulous and impassioned advertisement in the school paper referring to the “social disaster” that is Duke and encouraging students to speak out against the university’s purportedly racist and sexist atmosphere, in utter disregard of the due process rights of the accused. They also utilized local and national media to defend their abandonment of the presumption of innocence.

Even when the charges were conclusively demonstrated to have been false, the professors declined to issue an expression of regret for their hasty action (see Stuart Taylor Jr. and KC Johnson’s 2007 book Until Proven Innocent: Political Correctness and the Shameful Injustices of the Duke Lacrosse Rape Case. The book’s main title is taken from a phrase uttered by Duke’s then–president).

Or, perhaps, the very different faculty-and-administrative reactions are explained by identity politics: In 2006, the students falsely accused of rape were white and the accuser was black, whereas, on April 14, 2018, the alumni event was taken over by a variety of mostly minority students—and the antipathetic alums in the audience were, as one student put it, “some old white people.”

Either way, within a week after the alumni event was disrupted, the adult administrators took the student organizers’ cri de coeur seriously, for an update in the Duke Chronicle on April 21 noted that the investigation against the students had been abandoned.

Whew, that was a close call! Let the dialogue begin.

Either adult head-patting or adult drop-kicking over the far horizon is never going to adequately address this problem. In fact it is the understanding of this fact that I’ve come to believe raises the bar on adulthood most admirably.

Sometimes I like to ponder the fact that I came of age long ago but in such a tumultuous time nonetheless (not to me, but to my elders) and emerged out the other end of it (’round about 1975) relatively unscathed. That was then, and this is now. The biggest difference I see between the two eras, is that I was never “messed with.” An astonishing claim by today’s standards.

I tend to get on board with Douglas Murray’s overview, largely expounded upon during the writing of his fabulous The Madness of Crowds.

The brutal reality of the world these kids grew up in and now inhabit does not simply bear an Eden of easy fruit, as if they’re all Adams and Eves long before the fall.

They grew up in a world which presents an endless parade of things and consequences and causes and effects that they had nothing to do with, but which the adult world before them had everything to do with creating (much of if for fun and profit enjoyed by those who went before them).

This does not explain the entire story, nor does it intend to. In 1966 Chairman Mao unleashed some several dozens of millions of batshit crazy students of all manner and sorts, declared school out for summer, all seasons, and in many ways for the better part of a decade. You could hardly find space for a safe sneeze without encountering their confidence and their wrath, let along their sheer buoyancy and exuberance in being able to attack and bring down their elders, but also to destroy the world and culture those elders had helped to preserve. Which is where the batshit crazy part becomes so useful for mischief. Especially of the political sort.

So does this make the kids a bunch of pawns in someone else’s game? I’m still capable of enough skepticism to believe it’s possible. But we must still push back hard enough on the basis of simply this: if we expect them to enter life’s stage of young adulthood capable of acting the part (for their benefit as well as everybody else’s) we not only do ourselves a favor, but them as well.

We should not be surprised. They are simply little children — albeit large, bearded, sexually active, credit-surfing / debt-incurring, alcohol & drug consuming children with loud, whiny, highly-irritating voices… but children nonetheless. They cannot care for themselves; they cannot think for themselves. And we should certainly not expect that a simple warning that their tantrums would not be tolerated would actually serve to deter such tantrums. That would require the ability on the part of these large toddlers to put two and two together…to associate action with consequence. It would also require that there be grown-ups in the room, ready-willing-and able to provide such consequences.

C’mon now. This is Duke in the 21st century we’re talking about. Neither condition is present there in Wonderland. No, the students do not listen and cannot reason. No, there is no adult anywhere near the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party who is capable of actually linking a consequence of significance to such fascist misbehavior. There is only coddling, matched perhaps by a small but gentle scowl of disappointment.

Careful, though. I hear they’re running low on PlayDoh and Kitten Videos at the Student Center.

Those silly, pampered kids will have a hard time adjusting to life after college, where their feelings could be hurt again and again. Thanks for a sharp article!