Many years ago, in the late ‘90s, three professors and I met with the undergraduate dean at Emory University to discuss a Great Books proposal. Steven Kautz, a political scientist, led the effort, and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Harvey Klehr, and I backed him up. The idea was to build a Great Books track within the undergraduate curriculum whereby if a student took enough approved courses, he could add a certificate to his record. Kautz had lined up funding for the program and promises of cooperation from (to that point) three or four departments.

The dean was cautious. He wasn’t really a humanities guy, and none of us knew him well. Soon afterward, in fact, he left Emory to become head of the Bronx Zoo. Without his approval, though, we couldn’t move forward. He listened to Kautz’s pitch without any show of enthusiasm, simply nodding and posing a logistical query now and then. When Kautz finished, he finally made a substantive suggestion: drop the “Great Books” label.

The Sound of Superiority

He didn’t like the term. I recall him saying something about “Great Books” sounding superior or combative. Professor Kautz didn’t waver on the title, but he didn’t make much of an issue out of it, either. The suggestion trailed off, and we left the dean’s office without any determination one way or the other. As I think back on it now, I can’t conceive of anything we might have said after he offered his criticism that would have gotten past it and left our vision of the program intact. Obviously, we were there because we wanted a mini-curriculum of traditional, Western Civ works available for students interested in that kind of material.

Like everyone everywhere else, we had seen the core of liberal education erode as multiculturalism spread through the professorate and as “education” types called for more student choice in the general requirements for the bachelor’s degree. A policy that allowed a student to take a course on contemporary fiction instead of one on The Odyssey disgusted us. To object to “Great Books” was to ask us to drop our basic philosophy of teaching.

Perhaps that was his intent. A clever bureaucrat doesn’t kill an initiative by beheading it. He goes after a big toe, a small-seeming request or inquest that, in fact, disables the whole project or discourages the leaders of it.

But if that was the case, the resistance didn’t make much sense. After Western Civilization had suffered such a resounding defeat over the course of the 80s and 90s, it seemed bizarre or paranoid for anyone to worry about a tiny re-institutionalization of it. The modesty of our ambitions, which would only touch, most likely, 50 or so students per year, made the anxiety over the very name “Great Books” clearly overdone.

Nothing came of the proposal. Professor Kurtz left Emory awhile later and, I presume, took his idea and funding with him. I never spoke to him about it, but I’m sure the tepid, quibbling response to his initiative spurred him to search the job market for more congenial climes. He should have known better, though, and so should we. As anyone who has attempted such a program has seen, resistance on the part of campus leftists to small and non-competitive projects with a traditionalist flavor is a common occurrence. You must tread carefully to establish something that might smack of reactionary motives, even one that will be beneficial for all and won’t impinge on others’ turf. People are quick to express mistrust and worse.

The dean understood that, and his misgivings should have given us that lesson in resistance. But we could learn it only by not taking his words in earnest. He wasn’t speaking for himself. He was anticipating the reception of the initiative by our colleagues. Administrators, you see, are not the problem (Emory’s leadership has been quite helpful with conservative-oriented programs in recent years). It’s the other professors who don’t want to let it happen, no matter how unambitious the effort. A few weeks later, one of my closest friends at the time, an art historian who was gay and had close ties to Women’s Studies professors (I was still voting Democratic back then), told me that he’d heard Betsy Fox-Genovese was trying to push some conservative program under the radar. “Conservative” here meant “vile.”

The Moral Frame of Victimhood

The professors act this way because they are suffused with ressentiment. Ressentiment is, of course, Nietzsche’s term for a certain state of mind, or rather, a condition of being. He liked the French word because it signified a deeper psychology than the German (and English) equivalent does. Ressentiment is the attitude of slave morality, Nietzsche wrote, the moral formation of one who feels rage and envy but hasn’t the strength or courage to act upon them. A man of ressentiment knows and resents his own weakness and mediocrity, and he hates the sight of greatness, which only reminds the lesser party of his own inferiority. And so he fashions a new moral system whereby victimhood becomes a high badge, suspicion signifies a sensitive eye for justice, and group denunciation of lone dissenters is the surest path to virtue.

I am sure many readers of Minding the Campus have come across these types often in their academic careers. I’ve met them again and again, and a great error of my early academic career was to try to befriend them, or at least to try to lay out some common ground of collegiality. How naïve was that! You don’t ingratiate yourself with people who set their vindictiveness behind an exterior of sympathy for the disadvantaged and hurt ones among us. It obligated me to a degree of grubbing. The dynamic is never straightforward. They speak the words diversity and tolerance and inclusion, but they don’t mean them. In their mouths, those make-nice sounds are weapons of reproach. When you first encounter these colleagues, they seem tentative and probing, but not out of friendly curiosity about who you are. It’s a fraught examination of where you stand, for such creatures are acutely conscious that everyone takes a side, and they want to figure whether you’re with-us-or-against-us. Harold Bloom called them the School of Resentment long ago, and he was absolutely right. It took me awhile—far too long—to figure out that the chips on their shoulders had nothing to do with me, only with something they fancied I represented.

Defeating Male Writers

They won’t leave you alone because your very existence troubles them. One of Nietzsche’s best interpreters, Max Scheler, put it this way: “the origin of ressentiment is connected with a tendency to make comparisons between others and oneself.” They haven’t the integrity to be what they are, accept themselves, and affirm their status. They aren’t comfortable in their own skin. Other people keep reminding them of what they are not, and it bothers them. This explains the characteristic impulse to detract, to find flaws in George Washington and belabor sexism in Paradise Lost. Scheler again: “All the seemingly positive valuations and judgments of ressentiment are hidden devaluations and negations.”

When, for instance, during the Canon Wars of the late-80s a banner was unfurled atop the façade of Butler Library at Columbia showing the names “SAPPHO MARIE de FRANCE CRISTINE de PIZAN SOR JUANA INEZ de la CRUZ BRONTE DICKINSON” above the carved names Herodotus, Sophocles, Plato etc., the organizers weren’t celebrating a female tradition to go along with the male tradition. If that were the case, then students would know more today about the cultural past than they did before. The feminists would have ensured a curriculum that taught students male greats and female greats both. But, no, the real aim was to tear down the male lineage, to displace it and then to forget it. Students today know less about ancient Greece and Rome and the Middle Ages than they did during the ancient regime of the pre-60s. Multiculturalism didn’t enrich the streams of thought and creation. It only blocked the dominant one. And that was the point.

The bare presence of a Great Books program in one unobtrusive corner of the campus concerns them. They can’t help but draw comparisons. The organizers, few and humble though they be, presume to call their materials “great.” Who are they to say so? No question embodies the attitude or ressentiment better than that one. Who are we to judge? What licenses you to decide what’s great? And don’t you know that when you call some things great, you call other things not-so-great?

The adjective hits them as a challenge; their ressentiment asks them to take it personally. Great Books organizers don’t seem to realize that History passed them by, that they were routed and should NEVER return. In 1989, multiculturalists could get irritated and impatient with Great Books requirements. The War was still on. Ten years later, we were supposed to be past the whole shebang, as the title of a 2001 story in The New York Times captured so well: “More Ado (Yawn) about Great Books.”

Fewer Canonical Works, More Diversity

In the School of Resentment, it’s personal—it’s very personal. A couple of years ago, a distinguished literary critic and teacher in the New York area told me a story about a curriculum revision in his department way back in the early 90s. Several people on the faculty set about doing the customary thing—fewer requirements of canonical works and fields, more diversity. My friend, a solid liberal who would never, ever vote Republican, leaned over to the chairman before one meeting started and said something about the necessity of preserving the classics. The chairman said to him that in ranking the classics above other things, he was saying that people who teach the classics are better than people who teach the other things. My friend replied, “That’s one of the stupidest statements I have ever heard.” The chairman didn’t speak to him for five years.

People who suffer from this kind of resentment don’t like to lose. It’s not enough for them to win, either. They don’t even like to have any adversaries. They must defeat the other side, again and again, their envy ever unsatisfied by any single victory. This is the problem they have with Great Books programs. They make the eradication process more difficult for professors of the left. The professors have all the institutional power on their side, it seems, yet these old-fashioned, atavistic conceptions of tradition and greatness keep popping up like weeds through the concrete. They thought they won, and they did, but the triumph they needed had to be absolute.

It’s a tragic situation for them. Professors who sneered at the tweedy fellows who gave us standard editions of Dryden and Hawthorne, approached the traditional curriculum as if their moral make-up were so superior to that of the Old Times, and used diversity as a screen for tearing down the monuments . . . well, they chose the wrong battle. They seized humanities departments, altered the syllabus, and set identity politics at the core of disciplinary know-how, all in an effort to displace Great Books and the appreciation of them. But the aspiration to greatness is written in the human heart—as long as that heart hasn’t been warped by ressentiment (which is itself a twisted respect for greatness). Students and readers, young and old, still want them, and long after this generation of academics is gone, Great Books will be there to edify and entertain the next.

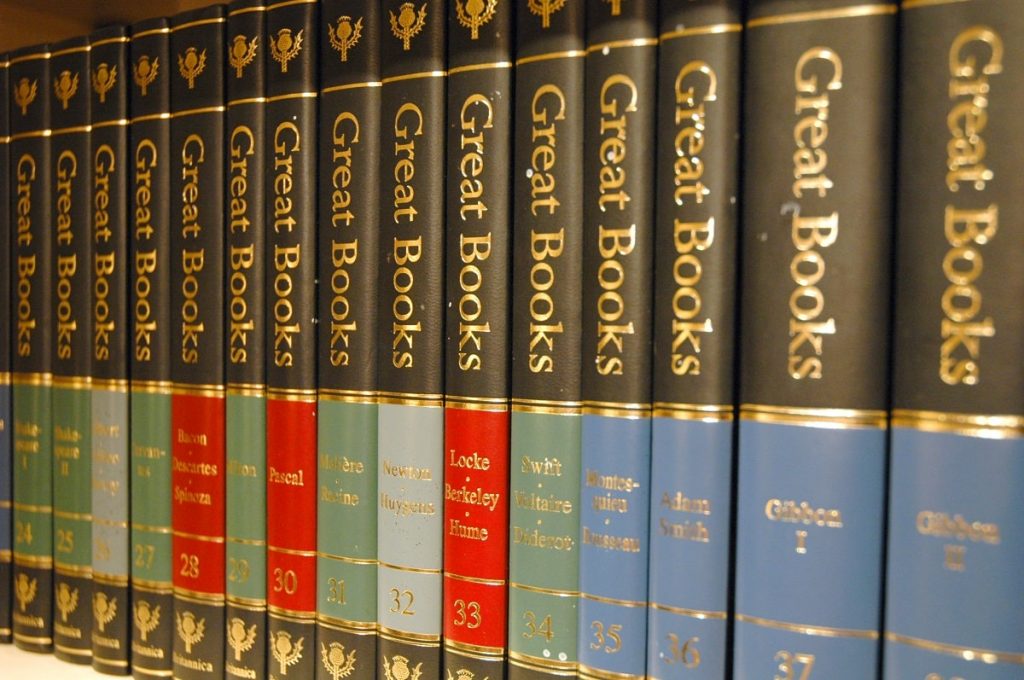

Image: The Great Books – Wikipedia

Thanks for sharing this valuable information. I support you. Please keep writing!

The biggest problem (besides race issues) in this Great Books business is that it is by far men who wrote them.

I’d like to challenge women (and women’s studies types) who object to these:

OK, you have an issue of too many men? YOU build the sewers, plow the snow, fix the power lines, build the frickin sky scrapers, STRING the power lines, build the manufacturing plants (or anything that’s being manufactured therein, for that matter). Oh, and start doing 95% of the defending of US ALL, and build the airplanes, tanks, etc. while you’re at it.

Oh wait, you’ve got your day aaaallllll filled up already: with complaining and criticism and a HUGE lack of appreciation.

It’s a sad commentary on the direction of higher education. But I wonder if a slightly different tack might’ve made a difference. If the professors had gathered student signatures on a petition to institute such a program and presented it to the dean, could their arguments have been more persuasive?

Your column is timely, Mark. At my Ivy, where a new Arts College curriculum is undergoing final revision (until the next Dean, the next touted rejigging initiative, the next reslicing of the curricular pie), we need not a Great Books program—though that would be my idea of enormous fun—but a Books program, simply. Throughout the campus, including the literary humanities here, the Digital Devilment is afoot, and no juggernaut was ever jollier or more implacable. I have wondered if a ‘Books Institute’ or even, quite seriously, a ‘Reading Minor’ or ‘Reading Consortium’ might afford, in some informal way, through some amassing of credits across courses, a chance for students and faculty to enjoy important (longer, older, often in verse, even) stories, essays, epics, poems, or whatever we might page through together, pencils in hand, and computers off. Have you, or any readers here, come across such an initiative, aside from the programs already in place at some small liberal arts colleges and what I understand to be a growing set of small denominational colleges?

I expect such a proposal at my institution would meet the same acerb apathy or shrugging recalcitrance as you sketch with your usual dash of vinegar in this lively column. I enjoyed reading it and will send it along to a few like-minded colleagues, also, like me, unassailably on the left, by the way, and who do indeed teach and revere great books in our secular, shabby-chic, close-reading, small-seminar, four-eyed way.

Thanks for what you wrote here; it gives me equal doses of hope and despair, which these days, is to be expected.

And so he fashions a new moral system whereby victimhood becomes a high badge, suspicion signifies a sensitive eye for justice, and group denunciation of lone dissenters is the surest path to virtue.

This is the key feature of ressentiment and the one usually overlooked by those who understand it merely as “resentment.” A perfect example of this is the esteem in which being black is held by the progressive left. On the one hand, they insist that being black is to be an oppressed, marginalized, voiceless, downtrodden, second-class, non-human (I’m sure I am leaving out some entries in the progressive lexicon). On the other hand, blackness is so coveted among white progressives that they will do anything to get real black people to award them the status. Think Rachael Dolezal. Think Toni Morrison proclaiming Bill Clinton the first black President.

Everything Bauerlein describes in this piece is true, which leaves me perplexed why conservative writers continue to behave as though our current politics is merely a great debate that can be “won” as against the Left by scribbling and reasoning and rhetoric and argumentation. What Bauerlein depicts is the Left’s will to power in action and in victory, and only a superior will to power coming from the Right will overcome it.

It is time, it is high time, for those like Bauerlein to abandon the progressive-controlled universities and assemble in force at a select group of other universities, there to teach the Western canon (which can, should and no doubt will incorporate black, Asian, and women writers, even those opposed to said canon, because the canon is first and foremost a continuing search for truth and knowledge) and–this is vital–actively keep out progressives of all sorts, students as well as faculty. No “_____ Studies” departments. No “affirmative action.” Develop and administer their own tests for admission. Ignore “accreditation.” Set up funding through private donors to offset the federal money that will surely be denied such universities. Over time–and it will take time–these institutions will become the new Harvards, Princetons and Emorys, while the originals will fade into cultural and economic insignificance owing to their transmogrification into churches for catechumens.

Perhaps I’ll take the time to compile a list, or lists, of that which the academic gestapo would prefer we didn’t read, study, etc. I think such lists would serve as a great study guide for my grandsons.

I take it that your sons like mine are too far gone?

Much of what is being said by this careful observer of modern university liberal professorship is the same issue facing those of us who are capable of actually analyzing and seeing the bigger picture and are appalled at their educated but short-sighted conclusions. Multiculturalism “feels” good when in reality the eventual result is a total disaster! Critical thinking requires a 360 degree survey instead of what is the best solution for making one feel one is being magnanimous. These oafs, disguised as professors, are a pox upon us all and would have us destroy our Constitution in favor of a more recent poll result; which too would not represent a true representation but a mere sample, shaded to confirm the Left’s view of how they “feel”.

First-rate article. Ressentiment pins it down nicely. It explains how the goal is exclusion of the Great, not admission of the Other. In fact, a prediction of this theory— which I think is confirmed— is that the books that replace the Great books will NOT include near-Greats, or overlooked Greats. Those would just continue to make the teacher feel inferior. Instead, the teacher will assign mediocre works.

Mencken said “To be happy one must be (a) well fed, unhounded by sordid cares, at ease in Zion, (b) full of a comfortable feeling of superiority to the masses of one’s fellow men, and (c) delicately and unceasingly amused according to one’s taste.” A mediocre academic has (a), if he loafs. Progressives prefer sensual pleasures to Mencken’s (c). And for item (b), it is necessary for them to feel superior not just to the masses, but to the Greats, and so they must purge them from their teaching and writing life.

And so I can’t imagine why enrollments are falling across college campuses nationwide. The people of which you speak will probably never realize what hit them when they get laid off or fired because there isn’t sufficient enrollment anymore. It will be the fault of the proles, of course, who can’t see the righteousness of their cause.

Thank you for the wonderful essay.

Adding a Great Books certificate to one’s academic record is a marvelous idea, and would perhaps be even better if it including a fancy gold seal affixed to the diploma.

Such a program might prove particularly appealing to those with STEM majors who sense that their training is one-sided. I was like that when I majored in electrical engineering. I responding by “cheating,” adding a host of electives that contributed nothing toward my degree. My department advisor would grumble, but do nothing to stop me. I always had an excuse ready.

But then I had it good. I was attending college in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when tuition was much lower than today. Staying frugal, I could cover (just barely) my education by working. I graduated broke but not in debt. My only frustration was that my degree did nothing to indicate those added courses. Engineering refused to allow us to have a minor alongside our major.

Today’s students are under intense pressure to graduate and pay off their large debts. They need more incentive than I did to take those added courses. Adding a Great Books certification would do that. Extending that to include a “Great Books” minor that meets the usual criteria for a minor might give them even more incentive. On top of a STEM degree such as a BSEE, they could add another set of letters that’d indicate their accomplishment.

Hi,

In Quebec City, we succeeded to build a little «Great books program» ten years ago. We have had 20 students each year. BUT the type of critics that you signal are just the same here (but in French!). One of the teachers of our team has just published a wonderful essay that responds to all the critics that we heard in the last ten years. If you read French, you definitly want to read it. It is called «La perte et l’héritage», by Raphaël Arteau McNeil. (Boréal, 2018)

“Great Books will be there to edify and entertain the next”

Only if they know about them.

Only if they are available on the Web.

You really think they are going to try and find BOOKS and that is Many Books.

If they don’t know anything about the Bible or History will they even understand what is in the Great Books?

The Great Books cannot survive in a vacuum. You must have the Back Ground knowledge to be able to understand them.

Mercer University in Macon, GA has a Great Books program and it is very well received by the faculty and students.

Professor Bauerlein does not mention it, but the negating impulse he describes here is surely a primary cause of the collapse of humanities enrollments. Nothing is more bitterly comical to observe than academic leftists puzzling over what right-wing conspiracy is to blame for our failure to attract students to a curriculum we ourselves have devalued.

So, is there a list of ‘Great Books’ that I can access? I’m just an old granny who wants to enrich my life. I read, but wonder if I could read better material. Also, when we keep the grandkids over the summer, I read to them every day for an hour or so. What should I be reading to them? They are now middle school age and I’m hoping I haven’t missed anything.

its what I’ve always suspected, liberals are mediocre people who want to bring everyone down to or below their level….how sad!

How deeply sad. The decline of wisdom is everywhere visible among the “Millenial” today. Flat eartherism is the least of it! (But there are plenty of comments on your piece, professor, at instapundit.)

I have read most of the great books and have too often found myself applying Twain’s essay on Cooper.

Old is not necessarily great.

There is way too much blah, blah, blah in the supposedly great books.

‘suspicion signifies a sensitive eye for justice’

Since you mention Nietzsche, it’s probably no surprise he would have a different definition of justice than any of these people. Heidegger said that Nietzsche’s ‘justice’ could only be manifested in art and knowledge. Since college professors of the type who would have a beef with Great Books produce neither, they can’t be ‘just’ per Nietzsche’s definition.

Even just sticking to Nietzsche’s words of justice as ‘the supreme representative of life’ would lead one to the same conclusion. Lol, those people are Last Persons (neither the men nor the women among them deserve either of those noble appellations, so let’s just call them ‘persons’. Lol again.) They’re so pathetic, they didn’t even kill a god, they just inherited a dead one and pretended like they killed it.

Best decision of my life was jumping off the humanities academic train just before it crashed into Identity Politics Mountain, i.e. at the same time events in this article take place. That one decision paid me more than any stock investment, in terms of money not not made. I have always told people one of my main motivators was that the professors I was getting to know socially were not happy people and, near as I could tell, it was all around “we are so smart, why don’t people give us more accolades”? The one person I know who was happy came from old money.

Could a person be a Nietzschean (not to the extent I was, where people knew to come to me to discuss him, but even casually) on campus today? Impossible, and while there are a lot of causes for that, one has to be the desire to start the history of ‘acceptable’ methodologies with Foucault to make sure someone ‘acceptable’ came up with the first one. Foucault is just Nietzsche in French, with more detailed discussions of sex.

This is my first online comment in a while, but the combination of historical timeframe, topic and Nietzsche quote made it all come together.

I demanded my son take the great books program, in return for financing his education. Toward the end of the program the school had begun to dismember the program. He got two solid, one weak and one senseless years. The school I could give not a flying cook about. The great books program was the best money I ever spent, truncated though it was. They’re scared, little, cheesy, gimps of the mind.

Excellent! Thank you Prof. Bauerlein for your piercing words against the tide of absurdity that has swept through academia! One can only hope that sanity and the desire for excellence will return those Great Books to relevance on our campuses!

Semper Fidelis,

A. M. Tang, II

“The organizers, few and humble though they be, presume to call their materials “great.” Who are they to say so?”

And to the ressentimenter, I challenge “Who are you to say no?”

Interesting insight. I think it has application across a range of professional disciplines.

Doug Santo

Pasadena, CA

Excellent column. I went to St. John’s College in Annapolis, the “Hundred Great Books” college.