William Deresiewicz is an essayist and author of two books, Excellent Sheep, the Miseducation of the American Elite and A Jane Austen Education: How Six Novels Taught Me about Love, Friendship, and the Things That Really Matter. He was born in Englewood, N.J. in 1964, graduated from Columbia, taught at Scripps and Yale and now is a full-time writer living in Portland, Oregon. He is a contributor to The Nation and The New Republic. This interview, conducted by Minding the Campus editor John Leo, took place on April 13.

John: You wrote a recent article on political correctness in The American Scholar which drew an unusually high amount of traffic and focused on the persistent attempt to suppress the expression of unwelcome beliefs and ideas.

Bill: The high-profile disinvitations of conservative speakers are probably the best example of PC. But much more pervasive is the constant policing of what everybody says on campus. Mainly the policing of peers by other peers. What they say, things they wear, the language they use. My students understood that there was always something new that they weren’t supposed to say, but they often didn’t find out what it was until after they said it.

John: You said that self-censorship is an easy thing to learn, particularly in dormitories.

Bill: Yes. Self-censorship sets in very quickly once you’ve been censored. And in the hothouse environment of a college campus where people are living in close quarters and very invested in the good opinion of their peers, it can be very intense. What’s missing is the core purpose of a liberal education, inquiry into the fundamental human questions, undertaken through rational argument, not the “ustalk” of PC consensus.

John: And then rather quickly in the article, you come to the conclusion that selective private colleges have in effect become religious schools. Explain.

Bill: I think one of the central ways this phenomenon can be understood is that those schools, in particular, are enforcing a certain ideology which has many of the characteristics of religion. And I mean I think it’s a useful way to understand it. I think it’s also an intentionally provocative way because part of that ideology part of that religion is itself to be anti-religious to be militantly secular and very hostile to religion and especially to Christianity.

John: Explain that dogma. I was just going to say you list some aspects of the dogma of this religion.

Bill: I mean obviously there’s a strong emphasis on identity categories and identity politics particularly the categories of race, gender and sexuality. There is also as I said the secularism itself and I think the last element I lift is environmentalism.  Now I should say, I mean some of these things are things that I share. I mean I believe that environmental concerns are extremely urgent. The problem is how it gets translated into a dogma rather than what should happen in college which is that people have genuine arguments and you might actually change your mind about things.

Now I should say, I mean some of these things are things that I share. I mean I believe that environmental concerns are extremely urgent. The problem is how it gets translated into a dogma rather than what should happen in college which is that people have genuine arguments and you might actually change your mind about things.

John: You say students seldom disagree with one another anymore in class. Why is that?

Bill: As one student said, we all have more or less the same set of opinions, so there isn’t that much to disagree about. Obviously, another aspect is this enforcement of a consensus so that if you do disagree, you’re often very reluctant to say so. And then I think that there’s a general sort of generational attitude that it’s really important to be nice and not confrontational and to support everybody. And you know disagreement, and certainly, the argument is seen as a form of aggression rather than disagreement.

John: And you say where there’s dogma there’s going to be heresy. Right?

Bill: Yeah. I mean one aspect of seeing these places as religious communities or religious institutions is how they deal with defense. When I say that there’s going to be heresy, I mean that that disagreement will be perceived not as a minority opinion but an impermissible and morally offensive opinion.

John: Right. And you say any challenge to the hegemony of identity politics will get you branded as a racist. As in don’t talk to that guy, he’s a racist.

Bill: Right. And again, I’m using a certain amount of hyperbole. But I’ve heard over and over again from students themselves that this has happened to them, or it’s happened to people that they know.

John: Talk about virtue. You mention there’s a sense that not only is the truth possessed but that the group or the religion is in full possession of virtue– we don’t just have perfect wisdom we embody it with perfect innocence. How does that work?

Bill: Well I mean again and let me also say that this is hardly something that’s confined to the left or to college campuses. I mean we certainly see this on the right. But I’m specifically concerned that it’s happening in colleges. And college is where it should not be happening.

So what I’m talking about is the very clearly embodied attitude, that we don’t need to argue about a large range of fundamental issues because we already know the right answer. But also, that because these tend to be social issues like identity, because we possess the right answer we are morally superior to those who disagree, and that’s why we are entitled to have content for them, to silence them, even to demonize them.

John: And you also say I’m jumping a little bit here that there is less interest in a critical mentality and learning about how to live a good life and how to develop and what you should do in life there’s less emphasis on that.

Bill: And what I’m talking about is the core purpose of a college education is to debate, to debate within yourself, what is true and good. So instead of debating, the questions that political correctness regards as settled are precisely the questions that college should open up to debate. And again for everybody, not just for people on the left but also for people on the right.

John: And the people who are unapproved or demonized on campus are conservatives, religious students, particularly Christians, students identified as Zionists, athletes and white males in general. Right?

Bill: Broadly speaking that’s correct.

John: How did that come to be. Why is the white male a demonized figure?

Bill: Well I mean this sort of grows out of a lot of the thought on the left for decades and it’s implicit in the premises of identity politics. It’s the idea that we live in a society that’s dominated by white racial supremacy and male gender domination. I actually agree with those premises. I do think we live in a society where there is still great systemic racism and great systemic sexism, and I think it’s foolish to deny that. The problem is what you do with that. I think one of the unfortunate things that political correctness does, especially in college campuses does, is that it stigmatizes individual white people and individual males and especially white men, especially straight white men. As if they were responsible for the systemic situation and that somehow by treating them as lesser it would it would actually help the systemic situation. This is revenge. This is confusing equality with revenge, but equality is not revenge.

John: And you say that race, sex, and gender are the dominant categories, of course, but what happens to class? In your opinion, class has not really been considered, right?

Bill: So what I go on to say here, I mean we can talk about everything we just talked about and the development of a kind of religion on the left, but in the second half of the piece I connect this to things I’ve written about with higher education before. Which is that what this really is about especially at elite college campuses is concealing the role of class, because class is the one identity category that we never talk about– not in society in general and not in a system of political correctness in particular.

But it is the purpose of elite colleges to reproduce class. They mainly enroll affluent students. And the purpose of affluent families sending their kids to those schools is to make sure that their kids remain affluent, so we’re reproducing the class. But obviously, if you are a liberal, if you’re a progressive, that would cause enormous cognitive dissonance. You would be embodying the thing that you’re pretending to fight — inequality. So political correctness provides a cover, and it enables you to say you’re actually morally virtuous because you’re against racism and you’re against sexism and unable to conceal the fact that all that may be true, but you are embodying classism.

John: I just wanted to say the politically correct culture, in lumping all whites together loses all nuance. You lose the Appalachian whites and other struggling whites who may have voted for Trump in rebellion against this regime.

Bill: That’s exactly right. Even before we get to working-class whites, as a Jewish person, I resent being lumped together with all of the white people because of my historical exposure; my personal experience is not the same as every white person. But you were talking about this other thing. So there’s a whole missing class on elite college campuses. The college campuses have, and I think admirably made an effort to include historically marginalized groups, people of color. I think that’s good. But then they can point to the socioeconomic distribution of their student bodies and say look, you know 10, 15, 20 percent of our students come from lower-income groups. Which isn’t very many anyway but, fine, it’s better than nothing. But the vast majority of those are non-white.

So 40 percent of America, which is the white working class, is essentially excluded from elite college campuses. You know, here or there you’ll meet someone from that background and they tend to feel extremely alienated. Because that class is absent from the campus, it’s possible to pretend they don’t exist. Which I think was the huge liberal mistake in 2016, or it’s possible to demonize them which was the other liberal mistake in 2016, they can be dismissed, they’re deplorable, whatever. So I think that there are real social and political implications of raising an elite in complete ignorance of this huge chunk of the country.

John: Your theme seemed to shift a little bit. Your theme that on the whole, the PC-infected people don’t study to learn about the human condition or to find their place in the world. Since they have a sense that they have all the truth they need. Is that fair? I mean I interviewed Harvey Mansfield last year, and he said something very similar about the kids at Harvard. He said they don’t think there’s anything more for them to learn. Which I thought was surprising then, but now it seems to make more sense in light of your views.

Bill: I think that that’s absolutely right. I mean listen let’s differentiate. They’re there to learn certain chosen and specialized body of knowledge I don’t think they would ever say that there are more to learn about biology or economics or English literature if that’s what they’re studying. But that’s sort of the technocratic education. That’s education to become an expert. That’s kind of said over again on one side. The side that I’m talking about that I imagine Mansfield was talking about is sort of self-knowledge is sort of social wisdom for lack of a better word. It’s moral knowledge. The sense that your own exploration about what a good person and a good society are has more room to go. I think that’s what’s not being, let me say, listen, I don’t think that’s anything new about being eighteen. I mean I was like that when I was eighteen. What’s new is that the colleges aren’t doing anything to disrupt it, for a variety of reasons some of which we haven’t really talked about.

John: If you were to project reform what would it consist of? What should we do about the condition we are in?

Bill: There are so many things. Partly because as we’ve been saying these things are rooted in some pretty broad problems. But you know, what I say in is that if we’re going to talk about campus speech, I think the rule of thumb should be the First Amendment. OK, so no speech codes. No disinviting speakers. If it’s permitted by the First Amendment, it should be permitted on campus. And if it bothers people that’s part of what free speech means. It means tolerating the speech of others even and especially when it bothers you.

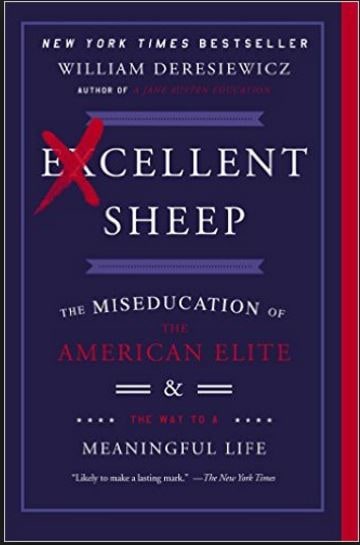

Beyond that, I certainly think that we need admissions policies that give preferential advantage not just to marginalize racial groups but also to class. I think we need class-based affirmative action in addition to or instead of race-based affirmative action. And then more broadly, and this is sort of what my last book, Excellent Sheep, was about. We’ve entrusted the training of our elites to a set of private institutions that will have their own interests that they will serve first. That training should involve broader leadership.

Instead, what we really set out to do in the 1960s and did all the way through the 1970s was have great, free public higher education. And if you look back at the colleges that each of the major party presidential candidates went to since Harry Truman in 1948, and for the first few decades after the war, almost all of them went to public universities. A few of them, like Truman, didn’t go to college at all. Since ‘88 they’ve all gone. Almost all of them have gone to private, basically Ivy League or equivalent colleges and graduate school.

This is a problem, but it’s a problem essentially created by the tax revolt. You know we decided that we weren’t going to pay for other people’s kids to get a good education. So you only end up screwing yourself, because you’re going to have kids some day too. And you’re going to want them to be able to go, not take out $50,000 in loans to go to college or not have to go to a public university that’s desperately underfunded.

John: Say something if you will about the leadership at the colleges. I run this site on the universities. We have a lot of articles on Yale, and we watch it pretty carefully. They run kangaroo courts, let the feminists expand the definition of sexual assault and investigate a professor without telling him and for some reason, have a major disruption over Halloween costumes–just amazing that a major university could behave that way. Do you know about that?

Bill. Yeah. Sure.

John: Well I thought what you said about the students being in the saddle all these days was what made me think about Yale right away because one of the students really abused the Christakises — husband and wife professors — threatened them, cursed them, and got no penalty at all for that, no suspension, no expulsion. Whereas the two Christakises were driven off campus. That sort of made me think of your comment that the kids are in the saddle now and the teachers are teaching with their tails between their legs.

Bill: That’s absolutely right. Take the Middlebury incident where their teacher was assaulted. I haven’t been following the aftermath carefully, but I don’t think anyone was expelled or maybe even suspended over that.

John: They said something would happen. They always say that. They said that at Berkeley. “Just you wait and see what we do.” That sort of thing and then there’s often a special commission that reports just the day before Christmas. I don’t think anybody’s been expelled anywhere. And the current routine is not to make any arrests, so nobody gets punished that way. So what do you think about that system?

Bill: Well here’s what I think about it because I dealt with it as a professor, at Yale and elsewhere. But it’s not specifically about what we’re talking about -– abusing teachers. But for instance, when students plagiarized they were never properly punished. And I remember one case where a student (it was the most cut and dried version of plagiarism you could possibly imagine). And when I reported it to the Dean, I said promise me that this time there’ll be consequences.

And of course, in the end, there were no consequences. These schools have come to treat their students as customers. They will almost never throw a student out, no matter what they do. They don’t want students to feel like they’re not going to graduate. Graduation rates are also a part of the U.S. News & World Report statistics.

No one’s ever going to flunk out at this point. Not going to happen. Even just giving students an F in one class is more or less impossible. And that’s the process. Once you’ve done that and once it’s become clear to students that they can basically get away with anything

John: Back up a little bit. It seems to me that in your analysis you’re really saying that the kids at the elite colleges are not really getting an education. Are you saying that?

Bill: Well. Yeah. I’ve said that.

John: Well then that’s a serious problem. If you can’t get a good education at Yale, Harvard or Princeton, where are you going to get it? And if something is that radically wrong, what should we do about it?

Bill: Well again let’s say a couple of things. First of all, if we’re talking about education in a narrow sense and a technocratic sense, I would not say that that’s not true. I mean they certainly are producing very well qualified scientists and blah blah blah. So that’s not what I’m saying. I’m talking about education of a different kind. Outside of the sciences, it’s often very difficult to really have an intellectually rigorous education. There are some schools still do it.

Reed College in Portland is one of those schools. There are other schools that I can name. It’s rare. It tends to be bad for business. But listen, I’m not sure that American society cares that much. People go to college to get credentialed. If it’s a prestigious college, they want a leg up. They want to be injected into the elite at high speed. These colleges still serve those purposes. I don’t think people care whether someone’s getting a rigorous education. Sometimes employers will complain, and employers have complained in surveys and studies that relatively few people they hire are really equipped to do the kind of thinking that they want them to be able to do.

John: But aside from the scientists, who have to deal with ideas and technical training, a lot of kids just float through the four years and then do nothing. Manhattan Institute, where I was for several years, got drawn into concern about education because employers in New York City couldn’t even hire kids for drudge work out of college. They just couldn’t function at all. So the quality problem stretches from top to bottom of the spectrum of brains.

Bill: It certainly isn’t a problem just at the fancy expensive schools. I don’t think that our public universities or third-tier schools are necessarily doing a good job either.

John: I wanted to ask you one or two questions about the earlier book Excellent Sheep, out in 2014. You were saying in effect that we have been churning out blinkered overachievers and conformists.

Bill: Yeah. Again there are exceptions but I mean, that’s right.

John: If you were doing that book again, how would you change it? Is there anything different that you would put it in now?

Bill: No, because I mean I’ve been thinking and writing, speaking, listening, reading about this for years before I wrote the book. Since then I would say the main thing that I’ve learned is just how widespread the things I described are. I mean I was talking about elite private and even elite public colleges. Say a hundred, hundred fifty institutions in the United States. Now it’s a broader trend.

What I’ve discovered is that a lot of what I’m talking about is true at many colleges in other countries and in K through 12 education as well. That is sort of a systemic problem. I blame the admissions process, still a big culprit. But really I think it’s about the way our ideas globally about education and what it’s for have changed. And if we see education simply as being in the business of producing workers for the job market, this is where we’re going to get. I mean it may be paradoxical because as you said, we’re not even doing a good job doing that.

I think it’s because we’ve set the terms so narrowly that we think that if we have kids solving equations 5 hours a day from the time they’re 6 years old we’re somehow going to produce good engineers. That’s not how it works. You need to produce a human being, and a human being is also going to be the best worker because there are going to be able to think for themselves. But we have you know we’ve tried to make education as efficient as possible. It’s like if a Martian were asked to design education that didn’t really know anything about actual human beings. So you try to leave out all the parts that supposedly aren’t necessary, but they are necessary.

And ironically you know we’re doing a lot of this because we feel the heat from our East Asian and South Asian competitors. They seem to be doing a better job. But actually, those very countries are looking at us and saying how can we become innovative? How can we move up the value chain so that we’re not just assembling products that are designed in California? And their answer has been we need our students to get more liberal arts. We need to be able to think flexibly and creatively. But we’re going in the opposite direction because we somehow think that those things are frills.

John: OK. Let me switch back to the earlier discussion. Isn’t there a long-term price to pay when you allow a culture to dominate the elite institutions and maybe even some of the publics based on racial antagonism toward whites. And sometimes Jews too because the BDS stuff has really gotten out of control. Don’t we pay a price letting that go on and not doing anything about it?

Bill: To me, the left just paid an unbelievably large price for this last year. I mean I’m not saying this is solely responsible for the election of Donald Trump. But you saw in Hillary Clinton in her campaign in the Democratic Party establishment the consequences of exactly what we’re talking about. People who really do think that the Democratic elite is out of touch not just with the people who voted for Trump, they’re out of touch with a lot of people who voted for them.

Among the elites are a lot of people completely ignorant of anybody who isn’t exactly like them, and they can’t understand how anybody could have a different opinion once you’ve explained things to them clearly enough. And I think it’s because their whole life their whole training their whole education has been in this bubble of other liberal elites whether it’s at the colleges or before that at the private schools or the wealthy suburban public school.

John: But I’m thinking in terms of the whole of American culture.. All my friends say don’t worry about these kids that are shouting down speakers once they get out in the real world, they’ll learn. What if the real world is like these kids, grown up? Maybe they can carry the adult world with them. What if there’s a huge lobby for the Supreme Court to find a big hole in the first amendment for hate speech.

Bill: Yes. I mean whether we’re actually going modify the First Amendment, I’m skeptical. I would say that we already see it in the culture at large. We see it in those parts of culture that are dominated by liberals. We see it in Hollywood. We see it in the conversation the liberal media. Listen, I don’t think conservatives have anything to feel smug or complacent about with respect to this because I think they enforce norms just as ruthlessly on their side.

But obviously, we’re all suffering from the fact that American society has largely been divided into two mutually hostile religions. Each of which is self-contained in this way. So yeah, I mean I think we’re paying that price. I don’t think left political correctness is solely responsible for it, but I certainly think it bears a lot of the blame.

John: Last question: Do you have any ideas for reform or to obliterate or at least dent this tendency of partisanship and the antagonism behind the PC ?

Bill: Well, I mean you asked me before about what colleges can do in terms of admitting more white working-class students, changing their own attitude about speech on campus, about how they treat their students as customers. I think the larger sort of polarization in American culture is going to be very difficult to address.

And I don’t think that there are easy solutions. I think that we need to I think probably on each side the left within itself and the right within itself we need to change the norms. And like I said in The American Scholar piece, radical feminists are attacking other radical feminists. So I think in general we need to listen even within our own camps as a way to start to begin to listen to each other. But the way you begin to listen to other people is by starting with a recognition that you don’t know everything and that you aren’t the most moral person in the world and we seem to be so addicted to moral superiority. I mean I think there’s some truth to the idea that this is America’s sort of Puritan nature coming out again. You know, everyone is a member of a tiny group of the elect.

John: Good. Thanks very much for your time, Bill.

It was easier for progressive students to be militantly in favor of free speech when the targets of that speech were the military-industrial complex, corporate capitalism, etc. They get to occupy the moral high ground. But when these students begin to see criticism of identity groups — or not even criticism, but simply ideas that are at cross-purposes with the received wisdom of intersectionality/oppression — they feel that they can only continue on the moral high ground if they absolutely agree with the ideas and/or values of any group seen as marginalized. As Deresiewicz notes, dorm life only intensifies the need to be seen as “on the right side.”

Yeats put it best: The middle shall cease to hold.