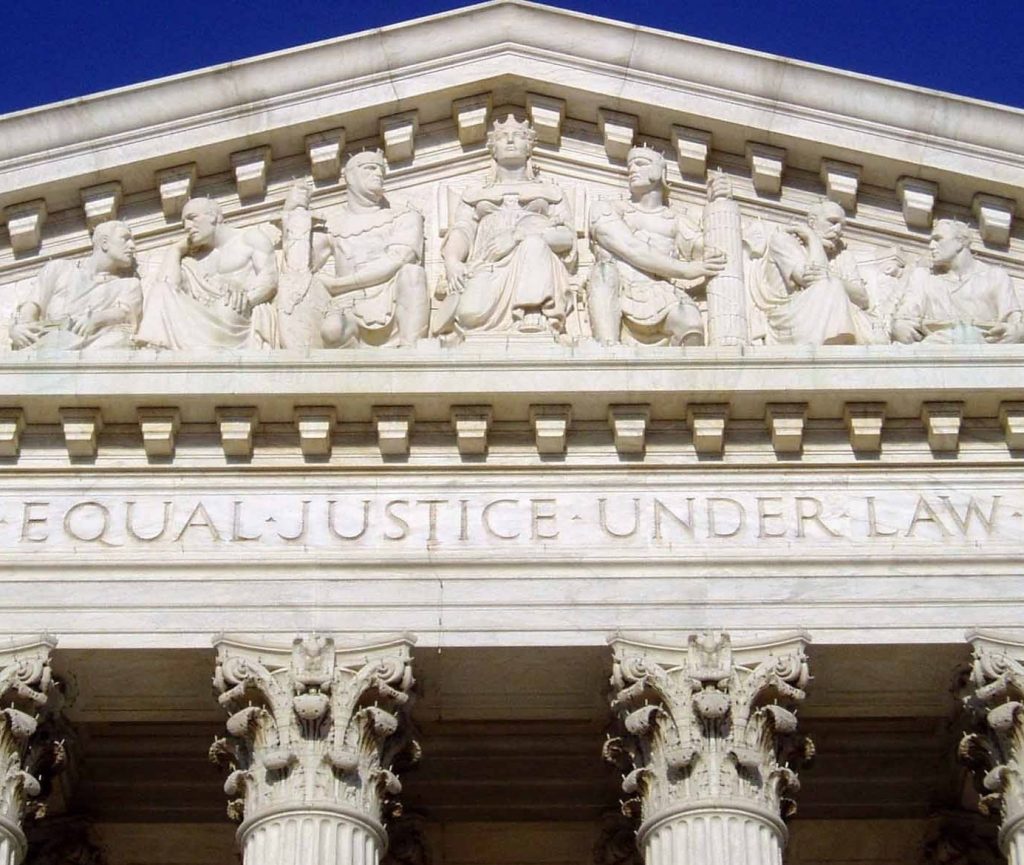

In campus sexual assault hearings, due process for accused students is rare, because of pressure from feminists and campus activists, administrators’ diffidence, and the Obama administration’s 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter that minimized protections for the accused.

Getting these cases into court for a due process trial is even rarer, but now the first such trial since the issuance of the “Dear Colleague” letter has ended with a victory for an accused Brown University student. Chief U.S. District Court Judge William Smith—as he had strongly hinted during oral arguments in mid-August—vacated Brown’s disciplinary judgment, arguing Brown had violated its own procedures, thus producing an unfair result.

Related: No Due Process, Thanks—This Is a Campus

The case involved student attempts to influence the judge, biased training of panelists in Brown’s sexual assault cases and the university’s extraordinary belief that flattery and flowers qualify as a manipulative part of sexual assault.

The case arose out of a fall 2014 incident where two members of the Brown debate team had oral sex after purportedly meeting (in a small room on campus) to watch a very late-night movie. In texts that flew back and forth between the two, the male student made clear his desire for no-strings-attached sex; the female was ambivalent, but signaled consent in some of her texts, while in others stating she wasn’t eager for sex. A few weeks later, the male student urged the female to put in a good word for him with a friend, with whom he wanted to have sex. These were not, to put it mildly, overly appealing characters.

Related: Don’t Bother with Due Process

In his 84-page ruling (which you can read here, and which both Robby Soave and Ashe Schow have also summarized), Smith identified three areas of misconduct by Brown (definition of consent, conduct of investigator, conduct of one of the panelists). Some of these issues were peculiar, related to the specific facts of this case, in which Brown had changed its policy between the time of the incident and the time the accuser decided to file her charges.

The decision has three areas of relevance, however, for matters beyond Brown. The first involves the “training” that the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) mandates all schools to provide to panelists in sexual assault cases. The equivalent in the criminal justice process would be if all jurors in rape trials (and only in rape trials) had to get training material—provided only by the prosecutors, designed to increase the chances of a guilty finding.

Anything Proves Sexual Assault

The inevitable result of this biased “training” manifested itself in the Brown case. After the incident, the accuser told a roommate what a great time she had with the student she’d eventually accuse; post-incident text messages sent by the accuser likewise indicated her having consented to sex. But one of the panelists, Besenia Rodriguez, said she didn’t consider the post-incident texts or conversations because her interpretation of Brown’s “training” suggested that sexual assault survivors behave in “counter-intuitive” ways. Therefore, she reasoned, “it was beyond my degree of expertise to assess [the accuser]’s post-encounter conduct . . . because of a possibility that it was a response to trauma.”

Rodriguez’s contention that her university-provided training shows that essentially any behavior—intuitive or counterintuitive—proves sexual assault “clearly comes close to the line” of arbitrary and capricious conduct, Smith noted. Yet the training Rodriguez received, and the mindset she reflects appears to be commonplace in campus sexual assault matters.

The case’s second key feature involves the pressure campaign—in the form of non-public e-mails—organized by a Brown student named Alex Volpicello. He even prepared a template—and dozens of students followed his lead and e-mailed Smith to urge him to uphold Brown’s handling of the case.

Volpicello’s ham-handed initiative predictably backfired with Smith. But the flurry of e-mails provided Smith with a glimpse of the witch-hunt atmosphere that exists on today’s campuses. He was deeply troubled, noting that “the Court is an independent body and must make a decision based solely on the evidence before it. It cannot be swayed by emotion or public opinion. After issuing the preliminary injunction this Court was deluged with emails resulting from an organized campaign to influence the outcome.

These tactics, while perhaps appropriate and effective in influencing legislators or officials in the executive branch, have no place in the judicial process. This is basic civics, and one would think students and others affiliated with a prestigious Ivy League institution would know this. Moreover, having read a few of the emails, it is abundantly clear that the writers, while passionate, were woefully ignorant about the issues before the Court. Hopefully, they will read this decision and be educated.”

Alas, the anti-due-process activists have shown no interest in education. Indeed, Volpicello issued a statement denouncing Smith’s ruling as indifferent to “the emotional trauma of the survivor” and insulting to “the intelligence and civic awareness of us as Brown students.” “Where is the justice?” wailed Volpicello. Where, indeed.

Third, despite the victory for the accused student, Smith’s ruling was very limited. He appeared deeply reluctant to involve himself in a campus disciplinary matter and explicitly said Brown could re-try the accused student—even as he spent page after page detailing Brown’s dubious conduct in this case. (And this comes after he spent page after page detailing Brown’s dubious conduct in another sexual assault case.) Nor did he pull any punches about the absurdity of Brown’s current policy, which defines sexual assault as including such behavior as a male student giving a female student flowers, or flattering her, in hopes of getting her to agree to sex. As Smith noted, Brown defines such manipulative behavior as sexual assault.

As FIRE’s Samantha Harris perceptively noted, “Smith’s opinion also makes quite clear that the court takes no legal issue with the substance of Brown’s new Title IX policy, which employs an affirmative consent standard and uses a single-investigator model to resolve claims . . . Courts are deeply reluctant to interfere in the inner workings of university judicial systems, particularly at private institutions . . . When we talk to the families of students facing serious misconduct charges at private universities, they often express shock at how easily the school can jeopardize a student’s future while giving him or her so few rights. This case, while a legal victory for the plaintiff, underscores this problem.”

In his opinion, Smith contended that he could strike down only a college disciplinary system that “tends to injustice.” If a system whose personnel regularly violate students’ rights, while defining the giving of flowers before sex as a sexual assault, and amidst a witch-hunt atmosphere doesn’t tend to injustice, what type of system possibly could?

The term Orwellian tends to be overused, but in these matters it is spot on. Are these administrators so blind that they cannot see the creeping reign of terror that they are fostering? All of these elite campuses have highly regarded law schools; don’t the faculty there recognize the dangerous erosion of due process by these Kafkaesque bureaucrats?