Ice cream cake has a disturbingly short lifespan in my home. When one is nearby, I ruthlessly hunt it down and devour it. Some days, when I have biked to work or gone for a run, I easily convince myself that I deserve cake as a reward. But exercise does not cause my cake-eating. It simply provides a rationalization for what I was going to do anyway.

Silly as it may seem, my cake-eating habit is similar to colleges’ habit of regularly raising tuition. When there are declines in state funding or increases in faculty compensation or college aid budgets, colleges often feel justified in raising tuition. But colleges raise tuition regardless of what happened to state funding, faculty compensation, or financial aid budgets. Colleges raise tuition because they cannot or will not resist the temptation to do so.

Bowen’s Five Laws

The best explanation for this tendency is provided Howard R. Bowen’s The Costs of Higher Education, which introduced the five laws of higher education costs:

- “The dominant goals of institutions are educational excellence, prestige, and influence.”

- “In quest of excellence, prestige, and influence, there is virtually no limit to the amount of money an institution could spend for seemingly fruitful educational needs.”

- “Each institution raises all the money it can.”

- “Each institution spends all it raises.”

- “The cumulative effect of the preceding four laws is toward ever increasing expenditure.”

Conventional wisdom explains rising tuition by pointing to the combined effect of 1) declines in state funding, 2) increases in faculty compensation (Baumol’s cost disease), and 3) increases in college-funded scholarships and discounts (institutional aid). In contrast, Bowen’s Laws imply that colleges will increase tuition regardless of what happens to these costs and revenues. My new paper, using data from the Department of Education, finds that tuition is likely to increase by a substantial amount even if there is no change in state funding, faculty compensation, and institutional aid per student.

For instance, from 2001-2002 and 2002-2003, the typical change in tuition at public four-year colleges was $396. Statistical analysis indicates that if there was no change in state funding, faculty compensation, or institutional aid, tuition was still expected to increase by $327. In other words, over 80 percent of the change in tuition would have happened regardless of changes in state funding, faculty compensation, or institutional aid. This finding contradicts the conventional wisdom, but is consistent with Bowen’s Laws.

Another piece of evidence that undermines conventional wisdom is the strong statistical evidence that changes in state funding, faculty compensation, and institutional aid do not have the presumed $1 for $1 relationship with tuition. At public four-year colleges, on average, tuition increases by $0.05 to $0.19 for every $1 decline in state funding per student, $0.07 to $0.40 for every $1 increase in faculty compensation per student, and $0.08 to $0.75 for every $1 increase in institutional aid per student. These estimates are generally far from the conventional wisdom’s presumed $1 impact for each.

Moreover, the statistical results indicate that the assumption of a $1 for $1 effect on tuition is not supported by the historical evidence. Using those more realistic estimates, on average, 75-91% of the change in tuition at public four-year colleges is left unexplained by changes in state funding, faculty compensation, and institutional aid.

An Irresistible Temptation

While Bowen’s Laws provide an accurate description of what colleges do regarding tuition (raise it), it does not answer the question of why colleges want to raise tuition. The answer to that question is that they want to spend more money, and they want to spend more because they are rewarded for spending more: They can recruit prize-winning faculty and top students, build better facilities, move up in college rankings, etc. But in order to spend more, they need to bring in more money, and one of the ways they can do that is by raising tuition.

This strange phenomenon stems from the dysfunctional nature of competition in higher education. The fundamental problem is that the quality of a college education is not known, which leads to two perverse side effects. First, without any measure of quality, colleges compete in a zero-sum game for relative standing based on reputation – a never-ending academic arms race. Second, as Bowen points out, without any measure of quality “it is easy to drift into the comfortable belief that increased expenditures will automatically produce commensurately greater outcomes.”

Trapped in an Arms Race

Thus, because educational quality is unknown, colleges continually attempt to increase spending under the belief that doing so will both improve their reputation and lead to better outcomes. But the goalposts are moving: their peers are increasing spending too. This academic competition puts enormous pressure on any revenue source, hence the phenomenal growth of fund-raising offices, the commercialization of research, and of course, skyrocketing tuition.

The moral of the story is that tuition increases because colleges are trapped in an endless academic arms race to spend as much as possible, and raising tuition is one tool that allows them to spend more than they otherwise could.

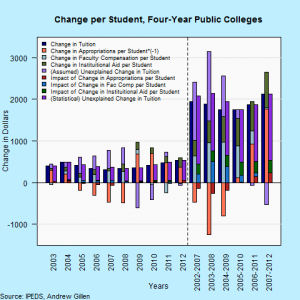

For each time period in the figure below, there are three bars with the same cumulative height equaling the change in tuition for that time period for the typical student (all values in these charts are enrollment weighted averages).

The first bar (dark blue) in each time period is the observed average increase in tuition during that time period (“Change in Tuition”). For example, in 2003, this value was $396.

The second bar for each time period consists of four components. The first three strictly enforce the conventional wisdom, meaning that tuition is assumed to increase by $1 for every $1 decrease in state funding per student (shown in the light red bar – “Change in Appropriations per Student*(-1)”), every $1 increase in faculty compensation per student (light blue – “Change in Faculty Compensation per Student”), and every $1 increase in institutional aid per student (light green – “Change in Institutional Aid per Student”).

The last component of the second bar (light purple – “(Assumed) Unexplained Change in Tuition”) indicates how much of the actual change in tuition is left unexplained, assuming the conventional wisdom is true. For example, in 2003, state funding per student fell by $302 per student, faculty compensation fell by $44 per student, and institutional aid increased by $35 per student. Assuming the conventional wisdom is true, this means that tuition should have increased by $293 (302-44+35 = 293). This leaves $103 of the $396 increase in tuition unexplained (396-293 = 103).

The third bar for each time period does not make any assumptions about the impact on tuition of changes in state funding, faculty compensation, or institutional aid. Rather it uses regression analysis to determine each factor’s correlation with tuition, which is then multiplied by that time period’s change in the variable to yield a more accurate estimate of the impact on tuition. For example, for 2003, the regression results indicates that a $1 decline in state funding per student is correlated with a $0.07 increase in tuition, so the impact of the change in state funding on tuition that year was $21 (the $302 decrease in state funding per student multiplied by the -0.07 correlation), shown in the red portion of the bar (“Impact of Change in Appropriations per Student”).

This same process is applied for the change in faculty compensation per student (blue – “Impact of Change in Fac Comp per Student”) and the change in institutional aid per student (green – “Impact of Change in Institutional Aid per Student”). The purple portion of the bar (“(Statistical) Unexplained Change in Tuition”) is the amount of the change in tuition that is left unexplained. In 2003, this was $368 out of the $396 change in tuition that year.

This figure clearly illustrates that there is strong evidence that changes in state funding, faculty compensation, and institutional aid are not able to adequately explain changes in tuition. The key evidence is the size of the light purple and purple components relative to the total change in tuition. Those bars indicate that a substantial portion of the change in tuition is unexplained even enforcing the assumption that the conventional wisdom is correct that changes in state funding, faculty compensation, and institutional aid all have a $1 for $1 effect on tuition.

On average, 25-33% of the change in tuition at public four-year colleges is still left unexplained even when assuming there is a $1 for $1 effect. The conventional wisdom does particularly poorly when state funding increases substantially (implying tuition should fall). For example, 99% of the change in tuition at public four-year colleges in 2006 is unexplained even after accounting for changes in state funding, faculty compensation and institutional aid.

For more details, see the full paper here.

At my alma mater, a private college, the changes in faculty compensation greatly lag tuition increase. So while tuition is among the highest among its peers, faculty compensation is among the lowest.

However, the number of administrators per student is among the highest, and the school pays its union employees nearly double the living wage for the area, and more than its peer institutions.

But in the end, when I was conversing with an alumni donation person on the rising spending, she came out and said that the school spends more on various things like administrative services and new fancy buildings because “students expect it” in competition with other school.

This blog article does not, as far as I can tell, specify whether the dollars are inflation-adjusted (and if so, by what kind of factor) or current dollars. Without this information it’s utterly impossible to make any sense of the claims made. The “unexplained tuition increases” might simply be eaten up by inflation. But there is no way to tell.

If these are inflation-adjusted dollar figures, there’s still a lot to be very dubious about here. But again, there is no way to tell.

I think the explanation is a lot simpler: Colleges keep raising tuitions because they can. Cheap government loans have goosed demand, supply remains constant, and so the market clearing price moves up. Colleges then find all sorts of good ways to spend the extra revenues, thus increasing their “costs.” Supply/demand curves to the rescue!