By Jonathan B. Imber

Until 1969, on the campus where I teach, all students were required to take two semesters of Bible, which made the Department of Religion a central force in the life of the institution. When I arrived twelve years later, with no Bible requirement any longer in place, the only remnant of a mutually reinforcing dynamic of religion and religiosity was the continuing office of the college chaplain. In fact, my first committee assignment was to the Chaplaincy Policy Committee. The chaplain sought the faculty’s counsel about how to integrate the role of the chaplaincy into the life of the College. Alas, in my early years, the Chaplaincy Policy Committee was eliminated, representing more than a lack of purpose. The truth was that the office of chaplain needed to be reinvented.

The Long Escape

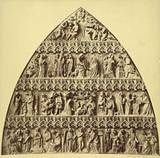

Before describing that reinvention, let me look back at one of the grand traditions of American Protestantism, which, after all, was the central force in the creation of most of the small, liberal arts colleges across America. In New England, until well into the nineteenth century, a large number of the men who attended these private colleges went on to become ministers. The public universities were already well ahead in providing opportunities for other occupations, but it was not until the end of the nineteenth century, with the founding of such universities as Johns Hopkins, that the shape and mission of most elite schools took on their modern and quite similar character.

Throughout the nineteenth century, in response to what was truly a pastoral faculty, students struck out on their own and developed what we know today as the Greek system. It was Athens vs. Jerusalem (and to be accurate, Jerusalem from the time of Christ onwards). These fraternities, today viewed as social clubs, were organized to escape what was regarded as an overly pastoral faculty, that is, a faculty dominated by well-educated clergymen who not only designed curriculum but also took upon themselves instruction in the moral life of their students. This effort on the part of clergymen did not prevent some very raucous disturbances among these students against their masters, but the evolution of the fraternity system was testament to both a long-term weakening of pastoral authority as well as a long-term increase in the role that popular culture would play in the lives of students. (The 1978 film, Animal House, was not just a parody of frat life but also an irreverent confirmation that “student life” had long since separated itself from any serious faculty oversight or obligation to assert such oversight.)

In the last two decades, particularly among the elite liberal arts colleges, the viability of fraternities has diminished considerably, with some schools ridding themselves entirely of their Greek systems. Defense of the institution of fraternities has pitted students against college administrators in a struggle that bears striking resemblance to earlier times, except that concerns about moral instruction have been entirely superseded by those about litigation. Hazing, alcohol-related deaths, assault, rape, and destruction of property are not just matters for litigation, they are activities associated with groups not traditionally associated with national or local fraternities. Sports teams, for example, which are ostensibly overseen by adult supervisory authorities, otherwise known as coaches, have come under powerful scrutiny, leading to both real and false charges of corruption and misbehavior. Obviously, schools with extensive sports programs and facilities are unlikely to eliminate them. Indeed, if fraternities had developed functions vital to the fiscal life of their host institutions, their fate, at least in some places where they have withered, might have been quite different.

Reinventing Religious Life on Campus

What is most interesting about the fate of fraternities is how their disappearance at elite liberal arts colleges parallels the reassertion of administrative authority over student life at the same time such authority is anything but pastoral. In other words, the new authority has had to navigate an entirely different landscape of identity and accountability. Religious identity has largely been replaced by ethnic and racial identities as markers of group membership and solidarity. The new organizations are often described as “cultural” to emphasize various aspects that may very well have emerged from specific religious traditions but without any moral squint. The now commonplace observation that such “culture” is about food and music and dance, about everything that can be shared as entertainment among different groups, conceals a decisive acknowledgment about what is forbidden to be shared.

Among students of Asian background, first- and second-generation Chinese, Korean, and Philippine students, the typical college campus offers very little to committed Christian students. These students’ worship and religiously-committed activities take place almost entirely off campus. To bring this point home, one of my students noted that her only on-campus involvement related to her religious commitments was leading a Christian A Cappella group on campus. Among the very few contacts with any administrators on campus was when her group sang one year at an Easter service. More importantly, as she remarked to me when I inquired about her involvement on campus, “I think that what our (and most other) religious life staff broadcast themselves as – which is a community that embraces all diversity – was not as attractive to me as a place of worship. It's not that I'm against interacting with others that differ in belief, obviously. I enjoy interacting with those of other religions or even those who are Christian but differ in particular beliefs. In fact, I have often had personal discussion with atheist, agnostic or other religious students about religious matters. But when it comes to actual worship service or “learning,” I do want to be studying, for example, the Bible in a way that is consistent with my theology. My particular beliefs and the embedded theology are the means by which I believe God has shaped me and humbled me.”

I should insist that the problem is not with the “religious life staff.” That staff and its work have taken shape over several decades, starting with the reinvention of what is now meant by “religious life” on college campuses. On the occasion of the former chaplain’s retirement in the 1980s, the opportunity to redefine (and reinvent) the role, dare I say, mission, of the chaplaincy was seized with considerable enthusiasm. One underlying tension, long before observant students of Islam became a campus presence, was between Christians and Jews. Jewish students were uncomfortable with what was broadly experienced as the Christian character of the institution. A legacy of intolerance and anti-Semitism could be confronted in a new way not only by eliminating the Bible requirement (by then nearly two decades in the past) but also by reinventing the purpose of the chaplaincy. Given the long-standing feelings of more than a few Jewish students about the ways in which they experienced Christianity on campus, it was really no surprise to me that when the President convened a dinner to discuss a new appointment of a chaplain, I found myself alone against abolishing the title of chaplain. I argued that the College had an opportunity to reaffirm its distinctively Protestant origins by hiring someone who could establish better and more faithfully how religious students could be part of a campus community without any of them abandoning their religious identities and commitments. I was admonished for believing that an ordained Methodist, Presbyterian, Baptist, Congregationalist, or Episcopal minister serving as chaplain could minister to all the needs of a growing diversity of students. Nevertheless, without abandoning the historic commitment to hiring a Christian minister, the decision was made to change the office’s title from chaplain to dean of religious life. A number of years later, the title became dean of religious and spiritual life.

The New Diversity

In such transformations of title the fate of “religious” life can be amply appreciated. As my religiously-committed student concluded, “I do not believe I am better than the person next to me, but I do believe that my God is the only God. I believe in tolerance, in that we ought not to use religion as a form of judgment, condemnation, of anyone outside of Christianity. But I don't believe that all religions can be true, or that pretending they can be is beneficial to us as a society. So there’s that. But my point is that when religion does become diluted, there’s really never a chance for answers to be fully given and thus never a chance to come to full understanding. Even when some claim that we have a right to fully express our religious views – we don't really. For me, it seemed much more meaningful to have personal in-depth discussions with students from different faith traditions rather than discussions where theology necessarily becomes diluted.”

Again, it is not surprising that what my student meant by “diluted” is what arose out of the 1980s as the drumbeat of multiculturalism, sometimes confined benignly to food and dance and other times rearing its ugly head in the form of identity politics and political correctness. The process of dilution in the end replaced one form of piety for another. The clearest message emerging from the transmogrified chaplaincy was that the smaller the religious minority, the more important it was to answer to its needs, though, for Jewish students the complications created by the increasingly intense hostility toward the state of Israel on college campuses had more to do with the hypocrisy of multiculturalism as one significant vanguard of political correctness. After September 11, 2001, the stakes were raised considerably, allowing for religious bigotry to masquerade as political conviction against both Jewish and Muslim students. Multiculturalism, it turns out, was often a monism, led by teachers as much as by students toward a paradise in which the old-time religious convictions of any sort had to be sequestered.

The addition of the title “spiritual” to the office of the dean of religious and spiritual life tells another story not simply of dilution but of a process of finding a common denominator to minister to students for whom the old term “multiculturalism” would be replaced by the latest monism, “diversity.” To minister has always had a therapeutic function. Soul-searching is not only about the weighing of conscience, it is also about the affirming of one’s faith. Spirituality is the kind of cultural buzz-word that gives wide space to all sorts of affirmations. That traditional faiths would be excluded from such affirmations is peculiar. The problem is how such affirmations are perceived by others. In this sense, some missions are more equal than others.

I do think that “diversity” is an improvement over “multiculturalism” because unlike multiculturalism, it appears on the surface to expand the range of possibly felt and experienced convictions and beliefs of students and faculty alike. Through fits and starts, the recognition of students committed to Wicca may seem absurd on the face of things, but it appears to expose the extraordinary hostility against the diversity within Christianity itself. At stake is a reconsideration of what it means to have “believing” students of any kind on college campuses today. A hundred years ago, students organized their fraternal systems to escape religiously-committed teachers and all that represented morally. Today, religiously-committed students conduct their affirmations of faith off campus, even as many other kinds of missions on campus are vigorously pursued, for example, environmental, political, and social ones. Students (and faculty) may openly proselytize their political convictions, including the expression of often slanderous characterizations of their opponents’ opinions. The sensitivities invoked about religious proselytizing are certainly a legacy of times past. The question that haunts higher education today is why this form of religious commitment, even apart from its missionary motives, remains so reviled now when the architects of the old order are no longer even remotely influential or are ever likely to be again.