Editor’s Note: This series is adapted from the new paper Higher Education Subsidization: Why and How Should We Subsidize Higher Education? Part 1 explored the justifications and rationales that have been used to subsidize higher education. Part 2 explored subsidy design considerations. Part 3 explored federal subsidies. This fourth and final part explores state subsidies.

State and many local governments also provide subsidies for college. At the conceptual level there are two main approaches to funding: funding either goes to the student in the form of financial aid or it goes to the college in the form of payments to the college, often called appropriations.

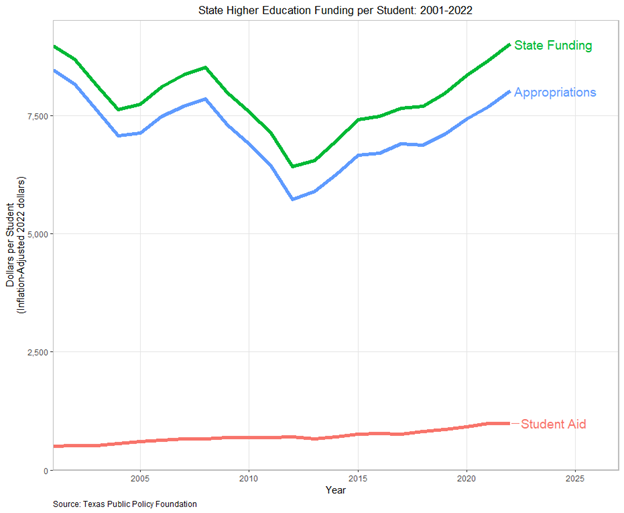

The figure below shows average per student state spending on appropriations, student aid, and the combined total—called state funding—from 2001 to 2022. Appropriations are and have historically been much larger than student aid. For example, in 2022, average student aid was $990 per student while the average appropriation was $8,022 per student, for total state funding of $9,011.

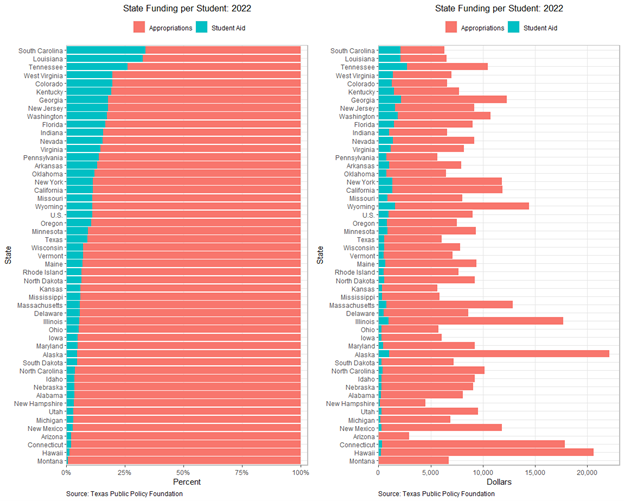

The next figure shows the breakdown of state funding between appropriations and student aid by state in both dollars (right panel) and percentage of state funding (left panel). Student aid is a minority of funding in every state, but a handful of states have either exceeded or are approaching 25 percent of state funding being devoted to student aid, with South Carolina, Louisiana, and Tennessee devoting the largest share of funding to student aid.

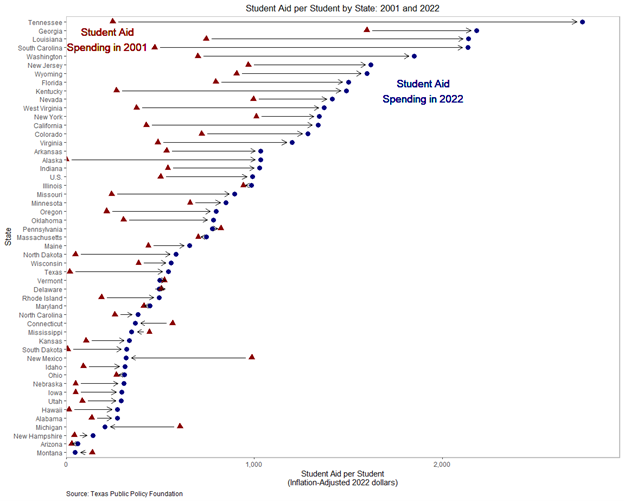

While appropriations are much larger than student aid, there has been a substantial shift toward student aid over time. In 2001, for every dollar of student aid that states provided, they provided almost $17 in appropriations. By 2022, this figure had been cut in half to just above $8. This trend can be seen clearly in the next figure, which shows student aid in 2001 and 2022 by state. Most states have substantially increased student aid funding over the past two decades, with Tennessee, Georgia, Louisiana, and South Carolina seeing the highest student aid funding in 2022. Only a few states decreased student aid funding, and only New Mexico and Michigan saw substantial declines.

The justifications for state—as opposed to federal—subsidies are varied, but redistribution and boosting economic growth are the most frequently offered rationales. The reliance on redistribution and boosting economic growth rationales raises concerns regarding subsidy design, though the concerns vary based on whether the subsidies take the form of appropriations or student aid.

Subsidy Design Concerns for Appropriations

Appropriations—state funding provided directly to the college—suffer from several design problems. To begin with, the redistribution and economic growth rationales both tend to favor selective rather than universal targeting. Targeting should be based on student characteristics—for redistributive subsidies—or the academic field being studied—for economic growth subsidies—yet when appropriations are given, they are provided universally, regardless of student characteristics or academic field.

To the extent that appropriations are selective, they are selective on an irrelevant basis, namely, the tax status of the college. Public colleges receive appropriations, but private colleges, generally, do not. This mistake essentially confuses the desire for government financing with the need for government operation of colleges. As Milton Friedman wrote,

The administration of schools is neither required by the financing of education, nor justifiable in its own right in a predominantly free enterprise society. Government has appropriately been concerned with widening the opportunity of young men and women to get professional and technical training, but it has sought to further this objective by the inappropriate means of subsidizing such education, largely in the form of making it available free or at a low price at governmentally operated schools. The lack of balance in governmental activity reflects primarily the failure to separate sharply the question what activities it is appropriate for government to finance from the question what activities it is appropriate for government to administer.

Friedman also noted that “restricting the subsidy to education obtained at a state-administered institution cannot be justified” because the rationale for the subsidy depends on the nature of the education being provided, not the tax status of the college. If an educational subsidy is justified, that justification does not somehow cease to exist if the student attends a private rather than public college.

In addition to being badly targeted, appropriations use the wrong method of distribution. Redistributive subsidies are almost always best delivered in the form of student aid, and economic growth subsidies also tend to operate better as student aid. Yet appropriations distribute funding to institutions instead.

The size of the subsidy is also likely inappropriate. State appropriations vary too much from state to state to be consistent with the main rationales for subsidization.

A final consideration with subsidies via appropriations is unintended consequences. Appropriations are often justified by claiming that high appropriations will keep college tuition low, on the assumption that if the college gets one more dollar in state appropriations, it needs one less dollar from tuition. The flaw with this assumption is that colleges’ costs adjust to their revenues, which means that higher appropriations will not necessarily “buy” lower tuition.

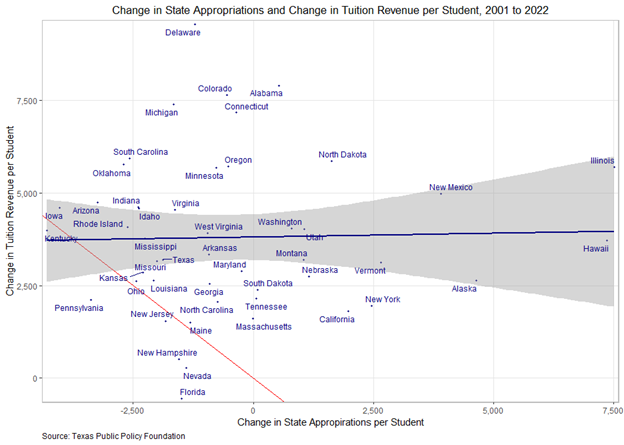

When appropriations increase, colleges can—and often do—pocket the state appropriations and then increase tuition anyway. Consider the figure below, which shows the change in state appropriations and tuition revenue by state from 2001 to 2022. If increases in appropriations “bought” decreases in tuition revenue, then each state should fall along the red line, which shows a $1 decline in tuition revenue for every $1 increase in appropriations. The actual relationship is shown by the blue line—with the shaded regions surrounding it representing the confidence interval—and shows no consistent—i.e., statistically significant—relationship between changes in appropriations and changes in tuition revenue—the 95 percent confidence interval for the slope is -0.22 to +0.26.

For example, between 2001 and 2022, per student appropriations fell by $4,292 in Kentucky, $2,615 in Rhode Island, $2,250 in Mississippi, and $953 in West Virginia, and rose by $798 in Washington, $1,055 in Utah, and $7,362 in Hawaii. Yet despite these vast differences in changes in appropriations, all these states saw essentially the same increase in tuition revenue—between $3,712 and $4,078. The unfortunate reality is that lower tuition cannot be bought with higher appropriations because colleges tend to pocket the appropriations and then increase tuition anyway.

In sum, state subsidies in the form of appropriations suffer from a severely flawed design. Given that redistribution and economic growth are the most cited rationales for such subsidies, subsidies should be selectively targeted and provided in the form of student aid. But appropriations are universally rather than selectively targeted among public colleges, while at the same time they are not available to private colleges at all. They are also distributed to the colleges rather than to students. The size of the subsidies varies too much as well, meaning that some states may be over subsidizing while others may be under subsidizing. Lastly, offsetting actions and behaviors on the part of colleges diminish the effectiveness of appropriations.

Subsidy Design Concerns for Student Aid

Subsidies distributed as student aid suffer from less severe design flaws than subsidies distributed as appropriations. The redistribution and economic growth rationales for state funding both favor selective aid delivered to students via financial aid—as opposed to universal aid delivered to institutions—and state student aid policies meet both of those criteria.

The main subsidy design flaw for student aid is the size of the subsidy. It is improbable that the optimal amount of student aid per student is more than $2,700 in Tennessee and just $46 in Montana. This means that some states are likely either over or under subsidizing student aid.

There is also a concern about offsetting actions and behavior. As noted earlier, student financial aid programs are often undermined by Bennett Hypothesis effects—colleges harvesting financial aid dollars either by raising tuition or cutting institutional financial aid—which convert the beneficiary of the aid from the student to the college. While no comprehensive studies have documented the extent of the Bennett Hypothesis for state-provided student financial aid, as discussed earlier, the evidence from federal student loans and federal tax benefits indicates that a substantial portion of student financial aid is captured by colleges, and this is likely to be true for state-funded financial aid as well.

States Should Transition to Funding Students Rather Than Institutions

While the federal government has chosen to mostly provide subsidies to students in the form of financial aid, states have chosen to provide most subsidies to institutions in the form of appropriations. As the previous section made clear, neither approach is perfect, but subsidies in the form of financial aid are generally the better approach, so states should transition their subsidy programs from appropriations to student aid. States could realize several benefits from transitioning from appropriations to student aid.

Student Aid is Better for Selective Targeting

The most discussed justifications for state subsidies for college are redistribution and economic growth. Both rationales imply that subsidies should be selective—universal subsidies would not be redistributive and different academic fields have different effects on economic growth, meaning their subsidies should vary. Subsidies in the form of student aid allow for the necessary selective targeting, whereas appropriations apply subsidies universally.

Student Aid is Better for Subsidy Distribution

Redistribution and increasing economic growth justifications also favor student aid. Given the goal of selective targeting, student aid allows for much more precise targeting of aid than institutional appropriations.

Student Aid is More Stable and Less Pro-Cyclical

Another advantage of the student aid approach relative to appropriations is that student aid is less volatile and is not pro-cyclical. States have historically responded to national recessions by cutting appropriations, at times quite dramatically. Yet student aid funding does not exhibit the same pattern.

Student Aid Does Not Suffer from the Bennett Hypothesis as Much as Appropriations

There is also reason to believe that student aid is more effective. Subsidies via student aid and subsidies via appropriations are both subject to unintended consequences in the form of the Bennett Hypothesis. But there is reason to believe the problem is worse for appropriations.

When states increase appropriations by $1 per student, this tends to be correlated with a 10¢ to 20¢ decrease in tuition. In other words, colleges appear to capture about 80¢ to 90¢ of every dollar devoted to appropriations.

For student aid, the capture rate varies based on the aid program. For Pell grants, which are means tested, colleges capture about 12¢ of every $1 by reducing institutionally funded financial aid, with no estimates of the amount they capture from raising prices. For student loans, colleges capture 40¢–60¢ through increases in tuition and up to 20¢ more from lowering institutional aid. There are some cases of colleges capturing all 100¢—e.g., tax benefits at low cost colleges—and for-profit colleges raising tuition by the entire amount of the aid increase. However, the typical result is in the 60¢–80¢ range.

Thus, in general, the Bennett Hypothesis is worse for appropriations than for student aid. Colleges appear to capture about 80¢ –90¢ for every $1 increase in appropriations, but around 60¢–80¢ for every $1 increase in student aid. While Bennett Hypothesis problems affect both student aid and appropriations, the problem is more severe for appropriations, which means that student aid is more effective.

Image by izzuan — Adobe Stock — Asset ID#: 834913601

One thing that is being overlooked here — partially because the distinctions have been muddied over the past few generations — is that there traditionally were three categories of institutions that states established and supported.

The first were the Normal Schools or Teacher’s Colleges — the initial purpose of which were to provide elementary school teachers. The normal schools needed to provide the humanities and the sciences and the rest because their graduates were going to be teaching it and hence needed to know it.

The second and third were the Agriculture and Engineering Schools — these are the Land Grant Colleges who were to teach “Scientific Agriculture and Mechanical Arts” (A&M) and there were three incarnations of the Land Grant Act, with the third being for the former Confederacy, but with the requirement that they at least provide “separate but equal” institutions for Black students, and this is where some (not all) of the HBCUs came from.

And then there were places like the University of Lowell (now UMass Lowell) that were established by the state to support specific industries — the Univ of Lowell to support the woolen and cotton mills that were then in the Lowell area, and it did a lot of work with dyes and other technologies that were of interest to that industry.

In all of these cases, the rationale was that the public benefits from having people educated in specific fields, and that the only way to accomplish this was to build and maintain colleges that provided education in the desired fields.

The distinction broke down in the 1970s when the normal and A&M schools wandered out of their traditional fields but at one point the state schools met specific state needs.

I consider it an abomination that taxpayers are funding worthless degrees like women’s studies, black studies and other similar “academic” areas. Nobody (other than the student and their so-called “professors”) benefit from this. And be aware that private schools also benefit from state funding in the form of reduced taxes. I sure all of the plumbers, commercial fishermen and truck drivers in MA feel honored to help subsidize the likes of Claudine Gay.

Well I come from a family of commercial fishermen and still have my Commercial (truck) Driver’s License (CDL) and my first thought is that we are glad to have folk like Howie Carr, who got his start with a journalism degree from a state school (U-NC). Howie’s on from 3-7 PM and you can literally drive from Rhode Island to the Canadian Border without interruption as you switch from station to station.

Before that, 12-3 PM, are Clay Travis & Buck Sexton who replaced the late Rush Limbough — Travis has a BA & JD, Sexton a BA and CIA experience.

Then there was the late David Brudnoy who had *two* doctorates and had the 7PM-Midnight shift on a Boston station that made it almost all the way to Bangor. There wasn’t much along I-95 but trees back then and truckdrivers were damn glad to have him.

Just sayin…