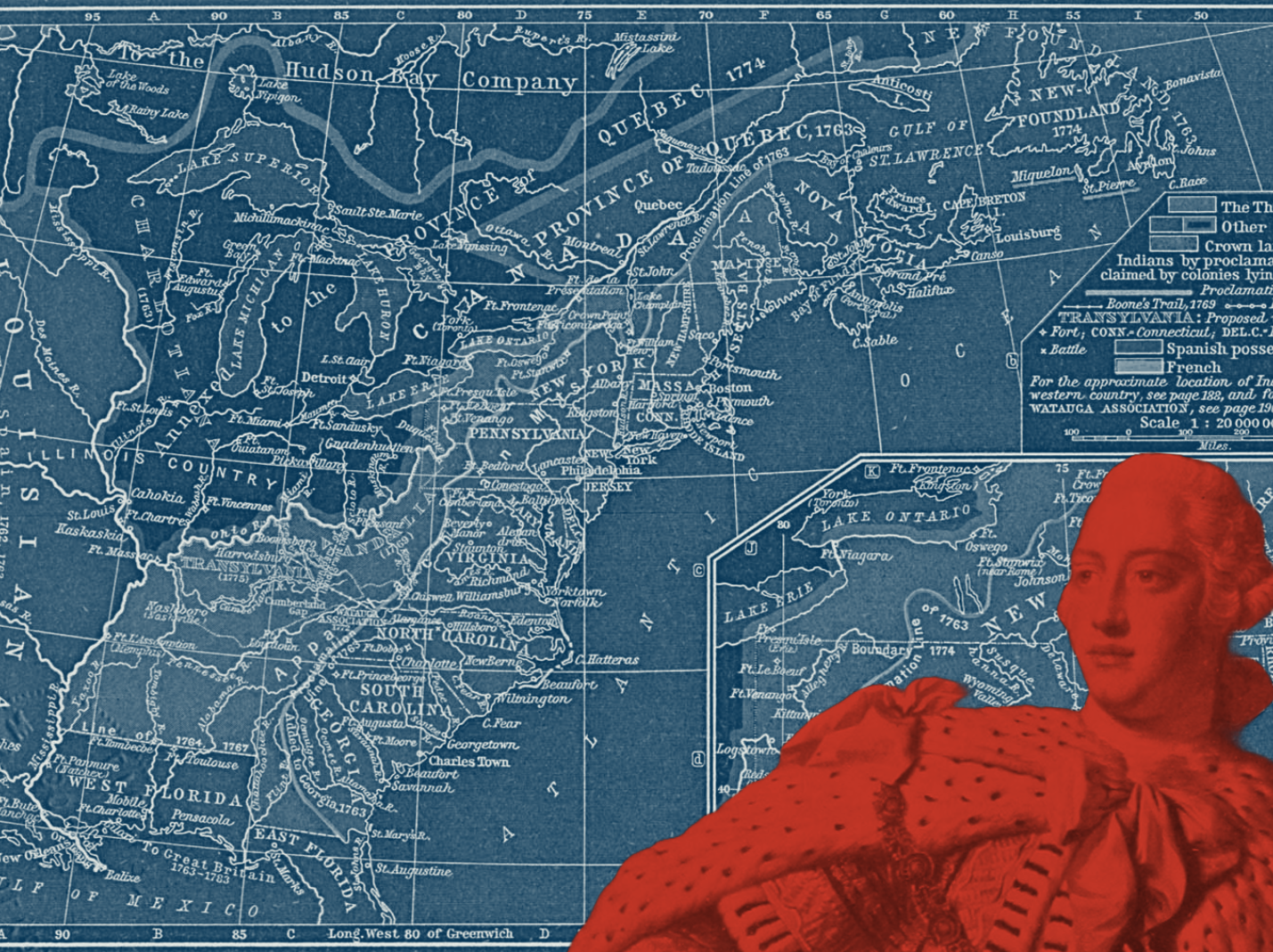

On June 22, 1774, the Quebec Act received royal assent. This, the climax of the Intolerable Acts, not only provided for greater accommodation of Catholicism and French law in Britain’s recently conquered colony of Quebec but also expanded its borders—to include virtually all of the trans-Appalachian West down to the Ohio River. It cut the possibility of further American settlement and expansion in a broad realm of Indian territory.

It was understood by the colonists as a scheme to limit the further growth of colonial American power—and to impose arbitrary French law to the American West in lieu of English liberty. As Thomas Jefferson put it in the Declaration of Independence, it was a grievance important enough to justify revolution: “For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies.” And whatever the motivations, it was taken to cripple the future prosperity of the American nation. A nation that could not grow could not thrive.

The closest modern analog to the Quebec Act is the Biden administration’s various attempts to straitjacket Israel so as to restrict further settlement of the West Bank. But, of course, Israel is not de jure a colony of the U.S. Yet American citizens do face an extraordinary and growing panoply of restrictions on their free use of the continent, which we gained by independence from Great Britain and—among other effects—the abolition of the Quebec Act as an inhibition on our westward expansion.

Much of the American West still belongs to the federal government, whether in the form of national parks, national forests, or some other ownership of land. The federal government always possessed a veto on Westerners’ use of most of the land in their states; increasingly, it exercises it.

Our labyrinth of environmental laws intrudes the federal government into ever-wider swathes of land it does not formally own. Say the federal government reintroduces wolves to a new section of the country—the laws protecting endangered species then make the federal government the overseer of every property owner who lives in a wolf’s howling range. Every environmental law is a present or future shackle on the free use of private property.

Federal housing policy, above all, Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, makes the government the bureaucratic overseer of every suburb in America.

I could multiply the bureaucratic regulations ad nauseam. All serve, in the end, to inhibit affordable family formation—to make it more expensive to marry, raise children, and live decently. The Quebec Act was intolerable because it threatened to make affordable family formation impossible for all Americans. We have a thousand laws and regulations that make up a new Quebec Act, inhibiting our own affordable family formation—our prosperity and the prosperity of our posterity—for generations.

N’est-ce pas intolerable?

Image by William Robert Shepherd — Wikimedia Commons & Internet Archive Book Images — Flickr & Edited by Jared Gould

I need to respectfully disagree with Dr. Randall — first, one must view all of this within the context of the infamous Expulsion of the Acadians (1755-1764), many of whom wound up in Louisiana and became the ‘Cagins. Generally considered to be a “Crime Against Humanity” and arguably an attempted genocide, they were French farmers living in what became Nova Scotia (New Scotland). After first taking their guns, the British attempted to round them all up and forcefully remove them — of the 4/5ths whom they managed to capture, about half died from disease, starvation, or shipwreck. The remaining fifth fled south into the uncharted wilderness of the St. John River Valley (this river is part of the current border between Maine & Canada).

Nova Scotia initially included all of what is now the Province of New Brunswick, and its border with the Province of Quebec is *approximately* the Maine/New Hampshire border extended north. But what really needs to be remembered here is that what the British were calling Quebec (and which the French had called “Canada”) was essentially the St. Lawrence River valley and the cities built along the river, including Montreal and the city of Quebec. (This is why you will see Quebec, PdQ (Province de Quebec), much as you will see New York, NY.)

This was the era of sail — people went places by sailing ships. Halifax, Nova Scotia (and now Yarmouth, NS) are roughly northeast of Boston, a straight sail across the Gulf of Maine and to this day trucks take a ferry from Yarmouth to Portland (ME) rather than going all the way around by land. By contrast, to access the St. Lawrence River one has to go around all of Nova Scotia, it is quite a bit further north.

And once you got away from the St. Lawrence River and the adjacent land that had been cleared for farming, you were in the woods. (You still *are* — this is the Great North Woods.) Yes, there would be the 1838-9 Aroostook “War” over the Maine/New Brunswick border (essentially the St. John Valley) but that would be 60 years later after the land had been settled by refugee Acadians & refugee Loyalists and found to be excellent land for growing potatoes.

And the big issue with religion was each colony being able to have its own official religion and no one imposing a different one upon them, as the British attempted to do to Massachusetts (e.g. “King’s Chapel”, etc.). Maryland was founded by Catholics, Rhode Island on religious tolerance — I don’t think the issue was a greater tolerance for Catholicism because Massachusetts and Virginia could tolerate each other in spite of *very* different approaches to religion.

I think the two bigger issues here was that the Crown was (a) attempting to gain/keep the loyalty of the Canadians and (b) reward them for their loyalty. The latter was particularly true in Nova Scotia where the Acadians’ land had been given to immigrants from Scotland (hence “New Scotland”) and people leaving New England — and notwithstanding the efforts of Benedict Arnold and others, Nova Scotia did not join the American Revolution.

(Now why would people be leaving the American colonies for a loyal British one in the runup to the Revolution???)

Yes there was the lingering resentment that the Crown wasn’t recognized they had fought the French on behalf of the Crown and westward expansion in terms of children and more likely grandchildren, but I think the real issue with the Quebec Act was a perceived unfairness, almost a child like perception of a younger sibling being treated differently.

And much of the Quebec Act made sense — they weren’t going to deport all the Quebecois the way they had the Acadians so let them swear allegiance to just the king. Massachusetts essentially had a church tithe (the municipal church and its minister was funded out of the municipal property tax — and if they were not going to have that fight with the troublesome Bostonians, why pick a fight with the Quebecois?

The Crown needed money and Quebec was exporting valuable furs and pelts — why not let them expand and increase this trade? Maybe they could get the Indians to be loyal to the Crown as well. (Look at what did happen 40 years later in the War of 1812.) Compared to the other stuff they had done that year, the Quebec Act really wasn’t poor policy — except that the Americans were already looking for a fight.