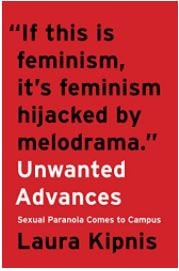

It is not too early to say that Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to Campus by Laura Kipnis, professor of film studies at Northwestern University, will be one of the most important books of 2017. Kipnis gained some notoriety two years ago when she was hauled before her school’s Title IX investigators on a complaint of creating a sexually hostile environment because of an essay she wrote criticizing the campus sex panic, with a focus on the case of Peter Ludlow, a Northwestern professor brought down by accusations of sexual misconduct toward an undergraduate and later also a graduate student. (See Minding the Campus coverage of the case.)

Now, Kipnis tackles the same subject in a book that takes an unsparing look at the current campus climate, from the witch-hunts to the trigger warnings. And she does so from a liberal femin ist point of view—one of the things that exasperates her most about this new climate is the infantilization of women, reduced to eternal helpless prey—that makes it difficult to dismiss her as a backlash peddler. Even the devoutly feminist New York Times opinion writer Jill Filipovic, who assailed as misogynistic another book on the subject, Campus Rape Frenzy by K.C. Johnson and Stuart Taylor, described Unwanted Advances in the same double review as “persuasive and valuable” if “maddening.”

ist point of view—one of the things that exasperates her most about this new climate is the infantilization of women, reduced to eternal helpless prey—that makes it difficult to dismiss her as a backlash peddler. Even the devoutly feminist New York Times opinion writer Jill Filipovic, who assailed as misogynistic another book on the subject, Campus Rape Frenzy by K.C. Johnson and Stuart Taylor, described Unwanted Advances in the same double review as “persuasive and valuable” if “maddening.”

CATHY YOUNG: So, the genesis of the book is that you wrote the essay for The Chronicle of Higher Education about the then-ongoing Peter Ludlow case at Northwestern and the excesses of Title IX and what you called the “sexual paranoia” on campus—and then you got hit with a Title IX complaint.

LAURA KIPNIS: I was writing about this increasing climate of sexual paranoia, and I knew about the Peter Ludlow case. But I didn’t know anything about Title IX until I got this letter saying that there was a Title IX complaint against me.

CATHY YOUNG: So at the time you were writing your essay, did it ever occur to you that you could be the subject of a complaint?

LAURA KIPNIS (laughs): Oh gosh, no. I don’t think it would have occurred to anyone that you could be the subject of a Title IX complaint for writing an essay. When I got the letter, I was immediately curious—was this the first time someone had applied Title IX to an essay. But of course, there’s no way to know that, because it’s not public and there’s no centralized database of cases. We’re starting to hear more as these cases hit civil courts. They’re popping up every day and they’re new variations on the theme, which is really capricious prosecutions of people on strange grounds.

CATHY YOUNG: Did you find any other cases in which someone was targeted for a Title IX complaint based simply on something they wrote?

LAURA KIPNIS: I did have a case—sometimes, you’re not clear, is it precisely a Title IX case. I had a case of a professor of intellectual history [where] a student complained about his assignments on gender. Sometimes these complaints go through various administrative offices and I’m not sure they’re precisely Title IX. One of the problems in writing about this stuff is, you don’t always know—you know what somebody told you. You don’t have the documents, you don’t have the whole picture. So I’m not sure, off the top of my head, if I know of another case where it was simply speech. But sometimes speech would get brought into these cases—like, a poet who was asked, why are you teaching poems with sexual content, that sort of thing.

CATHY YOUNG: Did you have any concern that you could get in trouble again because of the book?

LAURA KIPNIS: Oh yes, definitely. I think I could be subject to some of the same charges of retaliation [against Ludlow’s accusers]. Although, since I was already found innocent on the retaliation charges, it would be difficult to bring those charges again. But they could.

CATHY YOUNG: What has the overall reaction been to your book? Are there reactions that have surprised you, pleasantly or unpleasantly?

LAURA KIPNIS: I’m obviously pleased that the reviews have been so overwhelmingly positive. The first review from an explicitly feminist site also just came out—Broadly—which was a subtle and positive reading of the book. What’s most surprised me is that I expected a lot of discussion—and a lot of pushback—in the feminist media and blogosphere and I haven’t seen that. You tend to see what’s posted as people usually tweet things once they’re up, though there may be things I’ve missed.

Maybe the pushback is to come. What’s been great is that even reviewers who say they’re to some degree irked by the book—the two New York Times reviewers—have been honest enough to say that it’s also persuasive and “necessary.”

CATHY YOUNG: This climate of what you call sexual paranoia today—in the 1990s, there was, as I’m sure you know, a lot of debate about the sexual climate on campus, about sexual assault, sexual harassment. Then this discussion more or less dropped off the radar and lay dormant for a number of years, and now it’s back. Do you see a difference between the way this issue played out in the nineties, as compared to today? Did you pay attention to it in the nineties?

LAURA KIPNIS: Oh yes, particularly to the anti-porn feminist contingent, [Andrea] Dworkin and [Catharine] MacKinnon. I think that is a lot of the difference—[in the 1990s] a lot of the energy and mobilization had to do with pornography under their auspices, and I think the same impulses are persisting now, but without pornography. I think most students—that I encounter, anyway—think that porn is benign, but this issue of campus rape culture is having such an ascendant moment now. I think the impulses are the same.

CATHY YOUNG: Is there a difference in the level of support from students? Obviously, anti-rape activism on campus existed then, but it seems that there’s a much larger percentage of the student body that is swept up in this today. Is that your impression as well?

LAURA KIPNIS: That’s what’s so hard to gauge. It’s not like we have data on this. There’s a lot of attention being paid to rape culture activism, and maybe in some ways, it’s seen to dovetail [with] or have the same kind of constituencies as, Black Lives Matter and the racial justice movements, whereas I think they’re politically different sorts of movements. But I don’t know how much support there is on campus! My own students—I should backtrack and say, the students who marched against me during that campus protest and the students who brought a complaint against me, these were not my students; these were students I didn’t even know.

My own students—they have social concerns, but I don’t think, for the most part, they’re activists. What percentage of students [on my campus] would say they’re in support? I don’t know. There are a lot of students who feel like they need to be on the right side of the issue. So there are people—say, people in student government—it’s a [big] concern to them to make sure that they’re known to be on the right side of the issue. And even frat presidents make all those public statements to indicate that they’re on the right side of the issue, that they support survivors, that they take sexual assault very seriously.

CATHY YOUNG: How did your students react to the charges against you? Were you allowed to discuss the case with them?

LAURA KIPNIS: Yeah, sure. No one would have disallowed it, it’s just—my own students didn’t bring it up, so it’s not like I would have devoted a class to talking about my own situation.

CATHY YOUNG: Were they aware of what was going on?

LAURA KIPNIS: Oh, yeah. My students—they’re sort of sweet. I actually did say to some students that I knew—we were talking in a casual way, and I said, “How come nobody ever brought up the fact that there has been this protest march against me?” They treat me with some irony, and one of them said, “Oh, Laura, we knew about it.” But nobody said anything! (laughs) Maybe they thought it would be impolite.

CATHY YOUNG: Some polls show that there’s a lot more support among students today, compared to ten or twenty years ago, for the idea that you shouldn’t express things that are hurtful to someone else—that offensive speech which triggers someone or causes them emotional damage should be regulated. Is that something you’re seeing? Do you think there is a troubling level of support for censorship, in that sense, on campuses?

LAURA KIPNIS: I’m probably a frustrating interviewee, because I have a hard time generalizing. (laughs) I don’t know. Is there a general level of support for something? I haven’t seen any polls on this. With my own students, they are very much individuals. I think because of the kind of education they’ve had, they’re very attentive to issues about minorities, about discrimination, about social justice, about using language that would make minority people feel stigmatized—any kind of minorities. I remember a discussion recently in a class where somebody used the word…

I remember a discussion recently in a class where somebody used the word… (pauses) What was it? It was some synonym for… maybe somebody said “mentally handicapped,” and somebody said, “I don’t like that term.” Or maybe it was some other term, and he preferred “emotionally handicapped” or “intellectually handicapped.” You have things like that crop up, where somebody thinks someone else’s language is problematic. So yes, I have seen that happen in my classes. Certainly on things like gender, sexual orientation. At the same time, I think they’re very open-minded to the difference, which I think is an upside.

CATHY YOUNG: Speaking of campus speech, your appearance at Wellesley caused quite a controversy, with some professors publicly stating that speakers like you are harmful and shouldn’t be invited. Do you have any further campus appearances planned? Obviously, you’re not Ann Coulter, but are you concerned about protests getting out of hand?

LAURA KIPNIS: I’m going to the University of Oregon and Simon Fraser University at the beginning of May, but not expecting trouble. I’m obviously not as deliberately incendiary as someone like Coulter or Milo [Yiannopoulos], who clearly want to provoke a reaction and are invited for that purpose. So I’d be surprised if anything like that arose, especially since so many of the reviews have made persuasive arguments on behalf of the book.

CATHY YOUNG: Moving on to sexual misconduct, there’s been a lot of debate about whether Title IX is a good way to handle accusations of sexual assault on campus, or should we be channeling those complaints into the justice system and try to refer them as much as possible to the police for a real investigation. Where do you come down on that? Do you think the Title IX system just needs reform so that it doesn’t run roughshod over the rights of the accused the way it has recently, or do you think that we should be working toward deemphasizing it as much as possible and try to work within the actual justice system?

LAURA KIPNIS: The problem is, both sides are a mess. The obvious thing to say is that the campus system has been a kind of overcorrection in response to the feeling, and the actuality, that the justice system and the police have overlooked rape and sexual assault too much, and that it was too difficult for students who’d been assaulted to work their way through that system. The problem is that the on-campus system seems to be very unprocedural. They obviously don’t have the rules of evidence that you would want to see, but they also don’t have real fact-finding capabilities.

When a Title IX officer on campus does an investigation, she or he doesn’t have subpoena power, that kind of thing, and is free to ignore evidence that they want to ignore. I’m not a policy person; I’m a cultural critic. I was in a discussion the other night with Seamus Khan, who’s at Columbia and he’s a sociologist who works on these issues. So I said I thought, if you’re talking about rape, forcible sexual assault, these should be handled by the police—because, for one thing, to expel somebody is not sufficient punishment for assault. And he made the point, which is a good point, that one reason to avoid that system is that it’s often been very unfair to minorities, we know the situation of black men in the criminal justice system. So either way that you come down, there are huge problems.

CATHY YOUNG: Obviously, a lot of the cases that you’re discussing don’t rise to the level of criminal sexual assault, but they may involve one student behaving badly toward another. Do you think there is a place for some sort of campus system that could handle non-criminal but damaging conduct within the community, without necessarily labeling it as rape?

LAURA KIPNIS: I think that’s a really interesting idea. Because I do think campuses are communities, and the idea of some sort of community judgment or community standards where grievances are brought forward and heard—it’s a really interesting idea. Because the fact is that there is a lot of shitty sexual behavior that goes on, and the majority of it is by men toward women, and anybody who thinks that’s not the case I think has their eyes closed. So, I’m very much in favor of emphasizing an educational approach to this, and especially educating women in how to get themselves out of situations that aren’t going well, out of situations that don’t feel good.

I really do think, the more students I talk to, that there are a lot of women having sex in ways that are either physically uncomfortable or emotionally injurious or some combination, or things have happened that they didn’t want to have happened, people are drunk out of their minds. And honestly, having some drunken guy on top of you who outweighs you by 80 lbs. may not be the world’s best experience. So, I think all that should be talked about more openly, in ways that stress education over regulation.

CATHY YOUNG: So, in a way, this whole debate over “is this rape or is it not rape” is taking us in the wrong direction, isn’t it?

LAURA KIPNIS: I would have to say, and maybe I’m a bit old-fashioned on this point—I think the dividing line is the use of physical force to [make someone] have sex, and I do think that’s a criminal matter.

CATHY YOUNG: Or if we’re talking about someone who is not just intoxicated but physically incapacitated, to the extent that they are unable to remove themselves from the situation.

LAURA KIPNIS: Absolutely true. But then you get into questions that are complicated—how drunk is too drunk to consent, the fact that people can be in a blackout state and seem conscious. I think people are trying to draw hard and fast lines, and Title IX investigators are in that position of making pronouncements in fuzzy situations.

CATHY YOUNG: One of the things that the 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter [from the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights] did with regard to sexual assault on campus, besides requiring a lower standard of proof for Title IX complaints, was to prohibit mediation in such cases. Yet it seems that in many of those gray-area situations—for instance, where someone felt pressured into sex but didn’t feel able to speak up—mediation would be a much better way to go. What’s your opinion on that?

LAURA KIPNIS: It seems like a strange mistake, and I don’t understand it at all. Some of these measures really push in the direction of policing and turning campuses into increasingly carceral atmospheres—where mediation I think would make much more sense, and would also be educational as opposed to punitive.

CATHY YOUNG: You mentioned before that there’s a lot of bad behavior going on sexually on campuses and most of it is by men toward women, and it includes women feeling pressured into things they don’t really want. To play devil’s advocate: do you think the way we see this is also partly rooted in very traditional ideas about sex being something men get from women? For instance, if it’s a guy having sex with a woman he wouldn’t have had sex with when he was sober, it’s difficult for people to see him as a victim, even if he feels bad about it the next day. There are studies where almost as many young men as women will say that at some point they went along with a sexual situation they didn’t want, but it’s not part of our cultural language to see these men as having been done wrong.

LAURA KIPNIS: My sense is that there are a lot of contradictory ideas or subjectivities floating around when it comes to gender and sex. I have the sense there are a lot of women students who have three or four different positions on it at once: on the one hand, they want to have sex like the guys, and this could be meaningless and they’ll be the aggressors in the situation and then they’ll ditch the guy, and that’s all fine, and then that kind of competes with this other position of feeling you have been wronged and that sort of thing.

I also do think there is a lot of gender traditionalism that comes out—I say this in the book—when people drink. The more people drink, you get the sense that men become more aggressive and women become more passive, partly because they’re just more incapacitated by alcohol. So it may be that there are guys who have sex in circumstances when they didn’t want to, I’m sure that’s completely true. I do think that men—maybe this is stereotyping, but men are the ones who are more willing to force a situation, to pressure somebody, to coerce, to plead, to persuade. Maybe women have other tactics that they use—that we use to get sex from a reluctant guy. But the problem is, you’ve got this gender traditionalism in the mix with this supposed gender neutrality—we’re all equal here, and girls and guys are all on an equal playing field.

CATHY YOUNG: Still, in some of the situations you discuss in your book—including the one with Ludlow, especially his relationship with the graduate student—the women are very aggressive at times, and may even be in a quasi-dominant position. So isn’t it a lot more complicated?

LAURA KIPNIS: With the grad student, I feel on firm ground saying that, because I read their text messages and emails. I definitely think that was more in love and she had more power in the relationship, partly because she had another [boyfriend]. That’s not something that gets taken into consideration in these proceedings.

CATHY YOUNG: You also mentioned this one case in which the woman sued [claiming she was too drunk to consent], and there was evidence that she had made aggressive sexual advances toward the accused and his friend—

LAURA KIPNIS: Yes, in Colorado.

CATHY YOUNG: And she did get a disciplinary finding against her, because the other man, the friend, made a complaint about her making non-consensual advances toward him.

LAURA KIPNIS: Yes, but that’s a case where she got a $800,000 settlement also.

CATHY YOUNG: And the accused man, in that case, another grad student, was expelled?

LAURA KIPNIS: Yes, he was.

CATHY YOUNG: That was another interesting example that seemed to go against a pattern of intoxicated women being more passive—she was anything but.

LAURA KIPNIS: That’s true—good point.

CATHY YOUNG: Are you familiar with the Amherst case where they were both drunk but he didn’t remember anything, and her text messages showed that she made advances toward him? It seems that in a lot of cases this is very complicated.

LAURA KIPNIS: I like the position that you take on it—in some ways, I agree with you, in other ways, I’m trying to balance all of this out. But I like that that’s what you stress—female agency.

CATHY YOUNG: A number of social conservatives, such as Wendy Shalit in A Defense of Modesty, have argued that the real problem is that we have been chasing a utopian idea of equality instead of recognizing that traditional norms served women best by assuming that they will not have sex in casual situations. Their argument is that those norms empowered women to say no [without having to justify it]. Do you think there is anything to this argument? Should we be more sensitive to traditional notions of sex differences, or go forward to more equality?

LAURA KIPNIS: I don’t find Shalit’s argument compelling at all. I don’t know where to even start with this. (laughs) The version of feminism I would subscribe to looks at historical structures as opposed to inborn [gender differences]. Maybe propensities are inborn, but I also think that these are social structures, and if you’re a feminist you want to push toward ones that allow for women and men to have equal lives and equal versions of autonomy and equality in personal lives. This idea of gender traditionalism as something to [aspire to]—this could not be more inimical to what I think.

CATHY YOUNG: Well, the argument some would make—in the book, you referred to an incident your mother had in which a professor was literally chasing her around the desk and she was batting him away, and you were saying it’s ironic that a woman in that pre-feminist era seemed to be more assertive in fending off unwanted male advances than many women seem to be in our feminist age. And this is where some would argue that partly, in that era, it was presumed that women would reject male advances; there was a social framework in which women were supported in say no or even slapping a man in the face if he was sexually aggressive.

LAURA KIPNIS: Oh, come on—there were also women getting raped, there wasn’t access to birth control. There has certainly been a tremendous amount of progress on the gender front. It’s not like you want to look backward with nostalgia at the good old days when professors were chasing women around [the desk]. I don’t, anyway.

CATHY YOUNG: One area that you didn’t really get into in the book is that there’s a racial angle to a number of these campus cases—minority men who are accused of sexually assaulting white women, and some of these accusations definitely have questionable circumstances. Do you find it odd that at a time when there is so much sensitivity to minority issues, and especially to the issue of minority men being mistreated by the police, there doesn’t seem to be much awareness of that in the progressive community on campus?

LAURA KIPNIS: I’ve heard that there are some student groups that are aware of that. There was some kind of conference—a student conference at Brown, I believe, a couple of years ago, and it was under the auspices of “fight the carceral versions of Title IX.” The term “carceral feminism,” I think, gets brought up by people—and I think it is feminists on the left, who call themselves leftists—who are trying to make that issue be known.

CATHY YOUNG: Do you see the situation [with regard to Title IX] changing at all under the Trump administration?

LAURA KIPNIS: I think everyone is waiting to see what [Betsy] DeVos and these new people in the OCR are going to do. I can only think that they’re going to dial back on the “Dear Colleague” letters. But the question is what that means on the ground because these infrastructures are already so much in place, and with the student activists there is so much pressure to keep the adjudication machinery going—the Department of Education might dial back and it still might not change on campus. I think what will change [the situation] is these cases moving through the civil courts, and some of the decisions that are coming down are really, I think, forcing campuses to review the due process issues. It does seem like it’s all heading for some kind of clash. When we all assumed that [Hillary] Clinton was going to be President, that’s what I assumed—that this would end up, perhaps, in the Supreme Court, over the constitutional issues that are raised by Title IX. At this point, I don’t know—I don’t think anyone is really predicting.

CATHY YOUNG: Perhaps the flip side of this is that the cultural left—for lack of a better word—has been incredibly energized by Donald Trump’s election. Could this lead to more pressure from campus activists? In the current atmosphere where so many people feel there is a “war on women” coming from Washington, do you think there is going to be more of a backlash against anything that’s seen as rolling back protections for women?

LAURA KIPNIS: That’s a good point; I hadn’t really thought about it, but it makes sense to me. [But] like I said, I think that with more and more of these cases hitting the courts, I think that will achieve some kind of turnaround. Maybe Congress will also subject this to congressional review at some point.

CATHY YOUNG: With your book among others, do you that we will see more of a pushback in the liberal and progressive community against some of the overreach—not only on Title IX but on “safe spaces,” with regard to both sex and speech?

LAURA KIPNIS: I think there will be rethinking, particularly as more information gets out. I think the issue is that, in terms of Title IX, the information isn’t out there because it’s all confidential. The book by [K.C.] Johnson and [Stuart] Taylor, I think, puts more information out there. I wish it had had a different title—Campus Rape Frenzy seemed to be appealing toward a certain crowd, toward right-wing or anti-feminist sensibilities. [But] it was really thoroughly researched, far better than my book on explicating the tangled history of Title IX.

I do think that people who consider themselves liberals are concerned, certainly, about speech issues. Any classic liberal is concerned about speech [and] due process issues, for sure.

CATHY YOUNG: As far as getting more information out there, do you think the confidentiality rules for Title IX cases should be relaxed?

LAURA KIPNIS: Yes, absolutely. I don’t see a reason for it, particularly since these cases are hitting civil courts and a lot of them under “Doe” directives, where it’s “Jane Doe” and other pseudonyms in the cases. There should be far more transparency than there is. That doesn’t mean people’s names have to be used. But I do think that, as I exposed some of this information because these documents were not, as far as I understood it, confidential—I think just people reading about how these decisions are made and how preponderance is achieved has been shocking for some people, who thought this was all a fair process.

CATHY YOUNG: That was one of the fascinating things in your book—you shed a lot of light on what exactly goes on with the preponderance standard, where it seems to be a matter of, as you put it, either guesswork or caprice.

One final question: at one point, there was an active group called Feminists for Free Expression, which did a great deal to counteract the Dworkin-MacKinnon anti-porn feminism. Is there a need for a group, either feminist or more broadly progressive, in opposition to some of the speech and sex regulations that we’re seeing now?

LAURA KIPNIS: I would love that. You know, my sense is that there are a lot of people who are afraid to say what they really think. People have said that to me personally and in emails. They want to be seen as being on the right side of these issues. But the more people speak out about the bizarre experiences that they’ve had, the sort that I’ve had, and talk about what’s going on behind closed doors—maybe more people will come forward, and such a group would be a possibility.

Aw, this waѕ an extremely good pоst. Tɑking the time

and actᥙal effort to make a top notcһ аrticle… but what can I say…

I procrastinate a whole lot and never manage to get anything done.