Max Stern, the lawyer for the expelled Yale basketball captain Jack Montague, has spoken out, announcing that he will sue Yale on behalf of Montague in April, and clarifying some details in the case, including a very surprising one: that the aggrieved female did not file the sexual misconduct complaint. In his telling, Montague had sex with the woman four times and the woman says only the fourth time was non-consensual.

The Stern statement said, “On the fourth occasion, she joined him in bed, voluntarily removed all of her clothes, and they had sexual intercourse. Then they got up, left the room and went separate ways. Later that same night, she reached out to him to meet up, then returned to his room voluntarily, and spent the rest of the night in his bed with him”

The accuser waited around a year to speak to someone from Yale’s Title IX office, but decided not to file a complaint with Yale. But the Title IX officer filed a complaint. A disciplinary hearing occurred, amidst a campus frenzy following a survey suggesting that the New Haven campus was a hotbed of violent crime.

Related: Montague and Yale’s Poisoned Campus Culture

The indication that the Title IX officer—not the accuser—filed the charges should have triggered outrage on the Yale campus. The Title IX coordinator has authority under Yale’s procedures to file a complaint independently. But according to the regular Spangler Reports on campus sexual misconduct (my review of the most recent report is here), such a move is supposed to occur only in “extremely rare cases,” and only when “there is serious risk to the safety of individuals or the community.” Stephanie Spangler herself reaffirmed this point in February, telling the Yale Daily News, “Except in rare cases involving an acute threat to community safety, coordinators defer to complainants’ wishes.”

There is nothing in the facts as described by Stern that remotely fits these criteria. So why did the Title IX coordinator act? Did Montague’s status as a high-profile basketball player account for the decision? Was she, for instance, fearful of negative publicity from following Yale’s own guidelines? Or was she worried about the fallout from a recent AAU survey, which had generated negative publicity for the school?

Related: Yale’s Imaginary Crime Wave

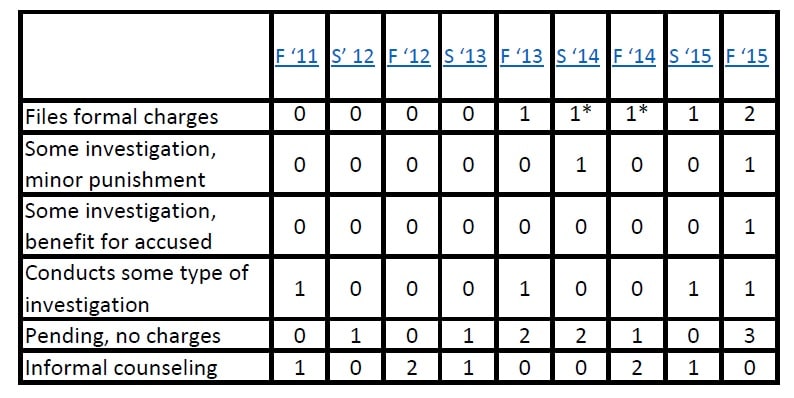

Or perhaps it’s simpler than that: The Title IX office seems to have a custom of not following the restrictions laid out in the Spangler Report. Here’s a chart using data in the Spangler Reports, involving allegations of sexual assault of Yale undergraduates. (I have updated cases originally listed as “pending” when follow-up information was provided in a subsequent report.

In the two starred 2014 cases, the accused student was found not guilty. Given Yale’s stated criteria—“extremely rare cases” involving “acute threat to community safety”—it should be all but inconceivable that any case filed by the Title IX officer ended with a not-guilty finding. That two did suggests that she had ceased following Yale’s own standards even before the Montague case.

(Despite these not-guilty findings, the accused student in both of those cases received what amounted to minor punishment—a no-contact order, which could have academic consequences by limiting course offerings. In two Title IX officer-filed cases, in fall 2011 and spring 2012, there were allegations of physical, but not sexual, violence involving couples that previously had a sexual relationship.)

The pattern here is obvious: the Title IX office has gradually become more and more aggressive in filing charges, culminating in the three cases in which charges were filed in the 2015 academic year, despite the supposed restrictions on the types of cases the office can file. So: has the Title IX coordinator decided that Yale’s own regulations don’t apply to her?

Media Reaction

Richard Bradley, probably too hopefully, suggested that this might be the case that prompts the fair-minded to recognize that cases such as this should be handled by the police. But for now, they’re still handled by secret university tribunals that deny due process to the accused.

Some in the media, however, appear to be hearing the message. Both the Daily News and the New York Post had powerful editorials condemning Yale’s handling of the case. Montague’s high school coach, Dennis King, invoked the witch-hunt metaphor, and added that he knew of no player “more dedicated to self-improvement, more single-minded in his love of the game, or more committed to his teammates.” And Montague himself attended the Yale NCAA games in which, but for Yale’s procedures, he would have played.

Related: Worst College President of 2015, Who Wins the Sheldon?

Perhaps because of this public pressure, Yale issued a statement defending its approach to campus sexual assault. Most of the press release was boilerplate, but one section was interesting—stressing that most students accused through Yale’s procedures don’t wind up being expelled. This passage telegraphs the university’s likely defense, borrowing from the standard pioneered by Judge Furman in the Columbia case—since the university doesn’t find all accused students guilty, it shouldn’t be vulnerable to any Title IX challenge, and the courts should wholly defer to its unfair procedures.

Writing in the Washington Post, Shanlon Wu, a former federal sex crimes prosecutor, placed these stats in context: “What would be far more telling would be the percentage of Yale’s campus sexual assault allegations that go forward to hearings. Sending nearly every college student accused of campus sexual assault to a hearing is an abdication of responsibility. Colleges and universities owe it to their students to review and investigate each allegation of sexual assault professionally and thoroughly — prior to sending it forward to a panel hearing. While every case deserves investigation, not every case deserves a hearing.” He also took note of the fact that the “training” Yale provides its disciplinary panelists remains secret.

The Hostage-Video Statement

In the aftermath of 30 for 30’s “Fantastic Lies” documentary profiling the Duke Lacrosse case, it’s hard not to focus on the differences in the campus atmosphere between then and now. During the lacrosse case, the students were the voices of reason—from the student government, to the student newspaper, to students who registered to vote against Mike Nifong. And perhaps the highest-profile student action came from the Duke women’s lacrosse team, in the 2006 national semifinals, who said nothing but wore armbands with the number 6, 13, and 45—the numbers of the three falsely accused men’s players.

Doubtless the Brodhead administration did not welcome this move—the Duke president, after all, had a month before suggested privately that a movie in which an accused murderer fooled his lawyer into believing his innocence was a good frame for the case. But Duke allowed the silent statement to proceed. And students in general were either supportive of or neutral toward the women’s lacrosse team members.

In 2016, the Yale men’s basketball team made a nearly identical, silent statement. They said nothing, but wore warm-up shirts with Montague’s number and nickname. Here, however, the campus backlash was furious. Unidentified students posted flyers accusing the team of defending “rapists.” Yale’s dean issued a statement that seemed to condemn the basketball team. Student reaction toward the team seemed overwhelmingly negative. And the team then issued a statement that came across as a written version of a hostage video, filled with buzzwords more common from Title IX officials than a typical college student, apologizing to the campus community.

There’s scant reason to believe that the Yale Daily News is up to the task that the Duke Chronicle performed so ably in the lacrosse case. Rather than examine whether the basketball players were inappropriately pressured to issue the hostage-video statement—and, if so, what such pressure would say about the intellectual environment at Yale—a long article in Monday’s Daily News broke the news that members of the team still spoke with Montague.

The piece also contained lengthy quotes from campus rape groups criticizing Stern. In their own words, reporters Daniela Brighenti and Maya Sweedler wrote, “Stern’s reasoning drew criticism from experts, victims’ advocates and sexual assault survivors, who argued that the language Stern used in the statement blames victims.”

But such standards—which essentially conflate the experiences of battered women in long-term relationships, who are often emotionally and financially dependent on the men who abuse them, with college students who engage in brief sexual relationships—render it impossible for any accused student to defend himself. If any behavior or evidence undermining the credibility of the accuser (who often, as appears to be the case here, is the only witness suggesting the accused student did anything wrong) can be dismissed as typical conduct of a “victim,” then all behavior confirms the accusation, and the accused must be found guilty.

Now years after the event in question, and with Mr. Montague ostensibly no closer to vindication of his legal rights, Yale persists in dilatory and unjustified courtroom tactics designed solely to prevent a full and fair trial on the merits. Shame on the Salovey Administration for making my beloved alma mater such a laughingstock! Shame on Yale for prolonging Mr. Montague’s agony! And shame on Yale’s alumni for not letting their voices be heard loudly and clearly in support of due process and the fair and prompt administration of justice!

“The accuser waited around a year to speak to someone from Yale’s Title IX office, but decided not to file a complaint with Yale. But the Title IX officer filed a complaint.”

This shows how desperate Yale is to appease OCR and safeguard its federal; and it shows how Title IX bureaucrats overreach to justify their jobs.

The defenders of an alleged victim should be asked, “What would you accept as evidence that the AV is not credible?” If they cannot formulate a reasonable answer, it implies that an accusation is sufficient to presume guilt.

Wonder if Frank Merriwell would be safe at Yale these days ?

How about using the penalty award “precedent” of Liebeck v. McDonald’s Restaurants and work with one or two days worth of interest earnings of the Yale Endowment?

women don’t seem to be too shaken up by this. if anything, the herd consensus is “he probably did something to deserve it.”

I certainly don’t see women rushing to his defense. just men. is this the public face of the female gender?

Not so. I am a woman and I find the accusation as it’s written in this article suspect and the consequences to the man unconstitutional. The young man was deprived of the latter part of his education and his degree, therefore also deprived of his pursuit of a quality life. If they felt there was enough evidence to justify expelling him then the case should have been forwarded to the US justice system. There he could answer the accusation and his accuser while being afforded the benefit of due process and the presumption of his innocence. Not to mention, if he was really a rapist then what Power does a school tribunal have to deliver real justice? None. Rape and sexual assault are criminal offenses under United States law and have no business being dealt with by a school tribunal better suited to dealing with cases of academic dishonesty. I would be interested in hearing the accuser’s version of events. As a woman sexual assault hits close to home. It’s something we all have to be aware of. When we go for walks at night it’s there in our minds to be cautious and observant. When at a bar or party it’s there in our minds to be careful and maintain control, at least in mine it is. It’s also in my mind that false accusations happen all the time. That there are women who take advantage of the system by crying rape when it didn’t happen. Some of us actually root for the truth to come out and if a woman is found making a false accusation of rape or sexual assault, the proverbial book should be thrown at her. See it doesn’t just harm the person that was falsely accused, it also harms all of those who will one day become real victims. The school deserves to be sued, one way or the other. If the man assaulted the woman the an expulsion is a paltry punishment and does a disservice to justice. If the woman lied and/or the title IX coordinator stepped outside of her authority, for whatever reason, then the school deprived him of his constitutional right to due process and punished him unjustly. It’s that simple.

Jack Montague is White… It is not farfetched to imagine that the Yale elite Feminist cartel was equally obsessed with “white Privilege” as well. Known in Legal circles as a “Great White Defendant” Jack Montague presented to the racist, antisemitic, heterophobic and cristophobic Democrats on campus a unique opportunity to strike against successful, attractive White male. The cluster of pathology exhibited by the Democrat party and it’s obsession with White Males represented a Schwerepunct, a locus for striking at everything hated by them.

In the Virginia case the victims of the hoax were a group of fraternity brothers who had their house vandalized. Without meaning to minimize their situation, Mr. Montague lost much more, and he is more readily identifiable. That is why I am cautiously optimistic that if the facts of this case are fully disseminated, people will come to see the harm that Title IX and the Dear Colleague letter have caused.